K.W. (Kyung Won) Lee and The Korea Times English Edition

Often referred to as the “godfather of Asian American journalism,” K.W. Lee is an award-winning journalist who remains an important voice in Asian America almost 70 years after he began his career. K. W. Lee was the editor of The Korea Times English Edition (KTEE) when Sa I Gu erupted. KTEE was an important outlet transmitting Korean American perspectives on the Los Angeles Civil Unrest to the English speaking public. Lee was vocal in his criticism of mainstream media that painted the unrest as a “Black-Korean conflict” rather than spotlighting historic and structural problems of racism, poverty and policing. To this day, he exemplifies the fierce pursuit of truth and justice through the power of the pen.

At the age of 21, K.W. Lee arrives in the United States as a student. He believed he would return to Korea to help run an English newspaper in the post Korean War era.

K.W. Lee begins working as a reporter for a local newspaper in Kingsport, Tennessee, reporting on Jim Crow issues in the South.

K.W. Lee becomes a cub reporter for the Charleston Gazette, reporting on coal miners who were suffering from Black Lung Disease in the Appalachia in West Virginia.

K.W. Lee in 1969, reporting on daily accounts of a West Virginia family’s life on isolated Doctors Creek.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of K.W. Lee

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 into law, effectively eliminating all immigration quotas per country and opening the process for the immigration of thousands of Asian immigrants into the U.S. Between 1965 and 1980, a total of 299,000 Koreans immigrated to the United States.

Korean immigrants begin to settle in the Mid-Wilshire area of Los Angeles, opening businesses and buying/renting homes in the area.

The beating of Black motorist Marquette Frye by Los Angeles Police Department officers sparks the Watts Riots, a mass uprising of Black Americans in the Watts neighborhood.

Eight days after the Watts Riots, Governor Edmund G. (Pat) Brown assembles the McCone Commission, launching an inquiry into the riots and its causes to ensure another riot does not happen again.

President Lyndon B. Johnson commissions the “National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders,” better known as the Kerner Commission, to investigate the causes of multiple “race riots” that took place across the country in the summer of 1967.

The Kerner Commission releases their report, citing racism by whites as the reason for unrest that took place in the summer of 1967. The Commission reports that “white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

President Richard Nixon declares the “War on Drugs” and Congress passes the “Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970.” It would later be revealed in a 2016 Harper’s Bazaar interview with a former Nixon aide that the War on Drugs was a strategic initiative to criminalize participants in the Anti-War and Black Power movements.

K.W. Lee, as a reporter for the Sacramento Union, reports on the wrongful conviction of Korean American Chol Soo Lee in the murder of Yip Yee Tak, a San Francisco Chinatown gang leader. K.W. Lee spearheads the pan-Asian movement to free him from prison.

Thanks to the organizing work of K.W. Lee and the Free Chol Soo Lee Movement, a Sacramento Superior Court Judge grants Chol Soo Lee a retrial.

K.W. Lee becomes the editor-publisher for the English language local newspaper, Koreatown Weekly.

Black unemployment and poverty in South Central L.A. rise as major employment centers for blue-collar workers close.

President Ronald Reagan makes significant cuts to Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) spending and gives states the option of requiring welfare recipients to participate in workfare programs.

Latino population begins to rise in South Central Los Angeles.

Korean Americans begin to purchase local businesses in predominantly Black neighborhoods like South Central. Many become owners of grocery stores, liquor stores, and gas stations.

As poverty and unemployment issues worsen in South Central, the crack cocaine epidemic begins to sweep the area.

The first “Koreatown” public sign is posted on the 10 Freeway near the Normandie Avenue Exit.

In the retrial of Chol Soo Lee in the murder of Yip Yee Tak, Lee is acquitted of all chargers and freed from prison.

President Ronald Reagan signs the Anti-Drug Abuse Act into law, establishing mandatory minimum prison sentences for certain drug offenses. This law was later heavily criticized as having racist ramifications because it allocated longer prison sentences for offenses involving the same amount of crack cocaine.

In Flatbush, New York, an eighteen-month boycott against Korean-owned Family Red Apple grocery store begins after the shopkeeper allegedly assaulted a Haitian woman in the store.

The Korea Times begins publishing an English edition of its newspaper with K.W. Lee as editor-in-chief.

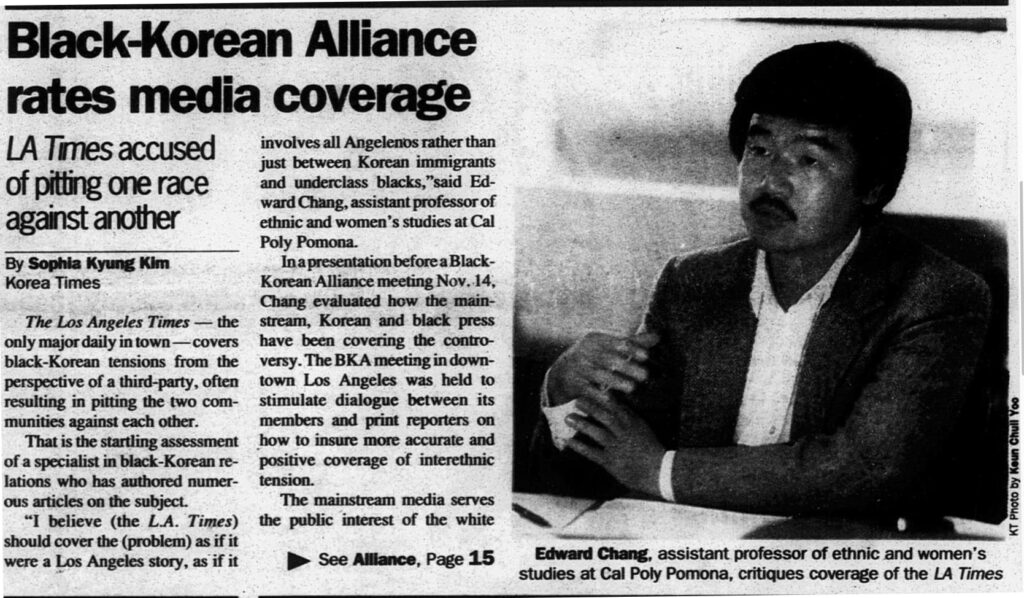

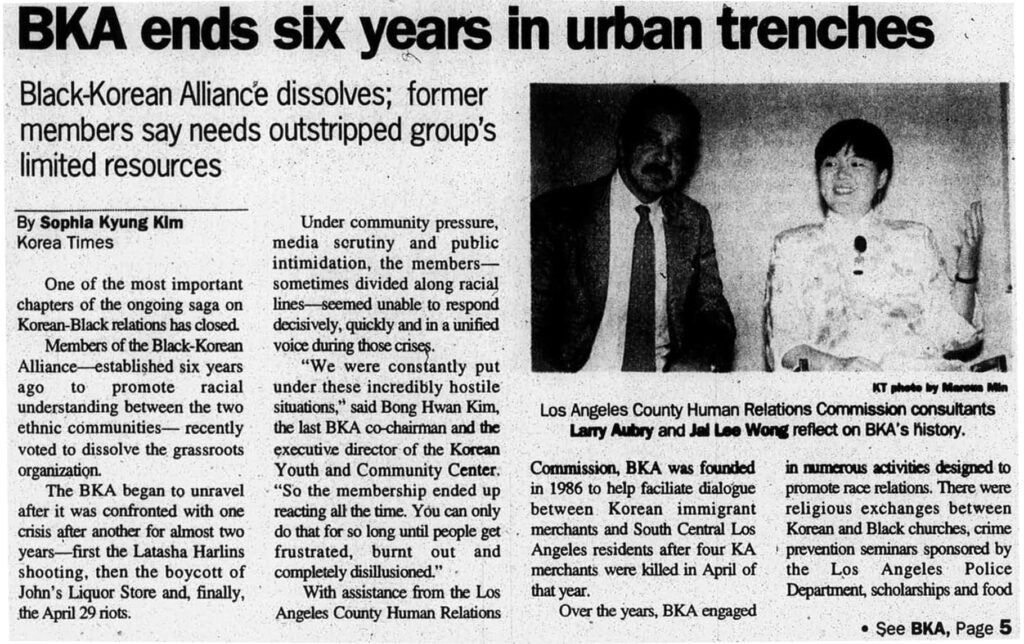

The Los Angeles County Human Relations Commission forms The Los Angeles Black-Korean Alliance to address growing Black-Korean tensions in South Central.

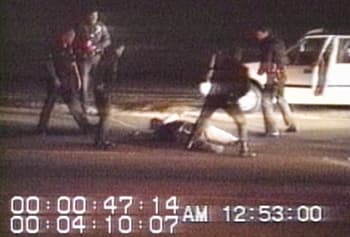

Home video recording captures Rodney King, Jr., a Black motorist, being brutally beaten by four LAPD officers.

A 15-year-old Black girl, Latasha Harlins, is shot in the back and killed by Korean shopowner Soon Ja Du after a scuffle ensued over whether or not Harlins was trying to shoplift a bottle of orange juice.

Lee, K.W., “Learn, Baby, Learn: Lessons from Latasha Harlin’s tragedy,” Korea Times English Edition, 1991-03-27, 7. ![]()

The Black-Korean Alliance and Korean American community leaders release letters attempting to address anger in the Black community towards Koreans over the death of Latasha Harlins.

“Statement of African American and Korean American community leaders,” Korea Times English Edition, 1991-03-27, 1. ![]()

“Statement of Korean American community leaders on the death of Latasha Harlins,” Korea Times English Edition, 1991-03-27, 7. ![]()

Mayor Tom Bradley launches the Christopher Commission, headed by attorney Warren Christopher, to conduct a “a full and fair examination of the structure and operation of the LAPD.” In their final report, the Commission would find that “a significant number of officers in the LAPD who repetitively use excessive force against the public and persistently ignore the written guidelines of the department regarding force.”

Lee Arthur Mitchell, a Black man, is killed by Korean liquor store owner Tae Sam Park in a dispute over payment of a wine cooler.

Fruto Reyes, Richard, “DA calls Mitchell case ‘clearly justifiable homicide’: Urging Koreans, blacks to fight crime, not each other,” Korea Times English Edition, 1991-07-14, 1. ![]()

Soon Ja Du is found guilty of voluntary manslaughter in the killing of Latasha Harlins. She is sentenced to 5-year probation, 400 hours of community service, and a $500 fine.

Fruto, Richard Reyes, “Soon Ja Du sentencing: Outcry over no jail term,” Korea Times English Edition, 1991-11-25, 1. ![]()

Lee, K.W., “An American Passage: Latasha becomes part of our collective conscience,” Korea Times English Edition, 1991-11-25, 1. ![]()

The Korean Immigrant Workers Alliance is founded, their first campaign would come after Sa I Gu/Civil Unrest, fighting for compensation for workers who were impacted by the destruction of their workplaces.

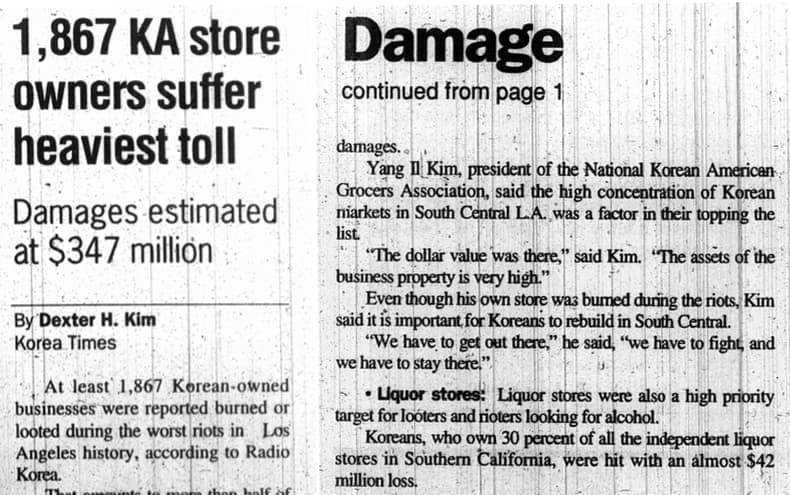

The four officers charged in the beating of Rodney King were acquitted on all charges against them, setting off unrest and fervor across South Central, beginning Sa I Gu/Civil Unrest.

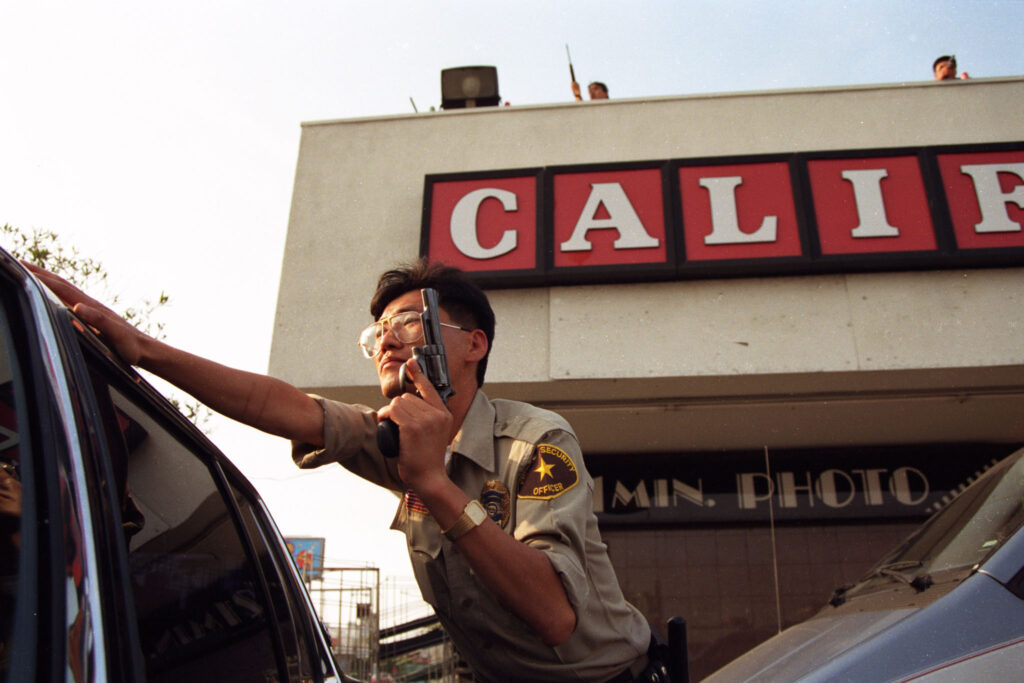

National news coverage of Sa I Gu/Civil Unrest depict Korean Americans defending their stores from looters, wielding guns atop building roofs and in parking lots.

Photo Credit: ©Hyungwon Kang/Los Angeles Times

Edward Song Lee, a Korean American protecting Korean-owned store from looters, is caught in a confused crossfire with LAPD and is shot and killed. He is the sole Korean American fatality during the unrest.

Fruto, Richard Reyes, “KA fatality during four-day riot: Community mourns for Edward Lee,” Korea Times English Edition, 1992-05-11, 1. ![]()

Fruto, Richard Reyes, “Mistaken identity cause in Edward Lee Death,” Korea Times English Edition, 1992-05-18, 1. ![]()

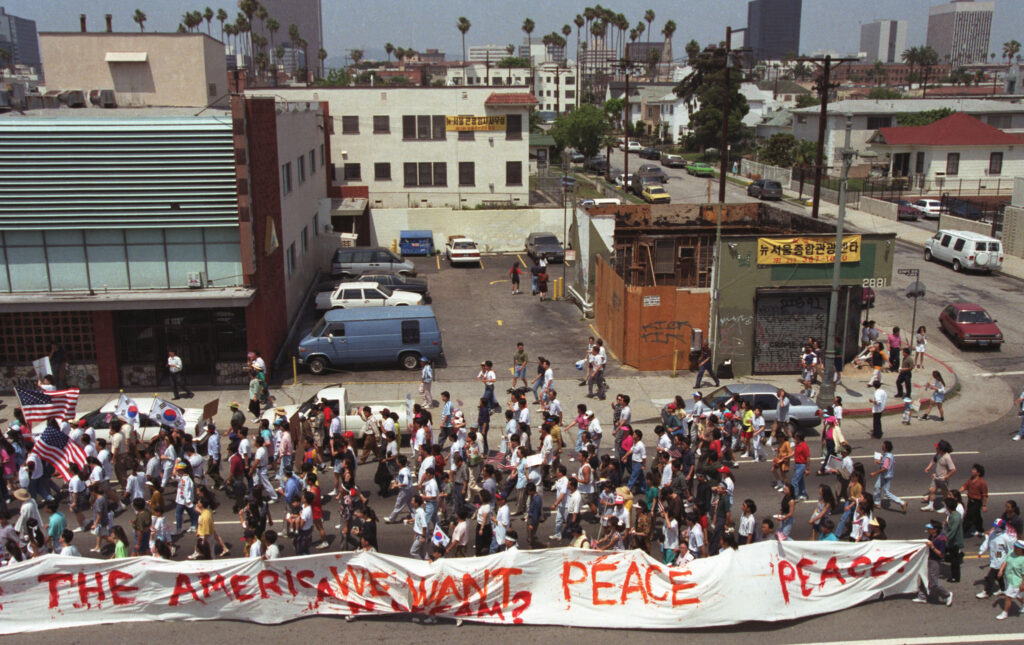

30,000 Korean Americans march through Koreatown calling for LAPD to be held accountable for their absence during the unrest and for peace in the city.

Photo Credit: ©Hyungwon Kang/Los Angeles Times

Korean American attorney and advocate Angela Oh appears on the television program “Nightline” to discuss Sa I Gu/Civil Unrest’s impact on the Korean American community, making her one of the most prominent Korean American leaders and spokespersons.

The Los Angeles Times reports that 51% of people arrested during Sa I Gu/Civil Unrest were Latino.

Korean American Bar Association organizes legal clinics to provide pro bono legal services to Korean American businesses impacted by Sa I Gu/Civil Unrest.

Mayor Tom Bradley announces the formation of a new organization, Rebuild LA. The organization is tasked to facilitate the regrowth of South Central and the local economy.

Korean Youth Center changes its name to Korean Youth and Community Center to reflect the community organizing work they were involved in after Sa I Gu/Civil Unrest and their dedication to serving a broader community.

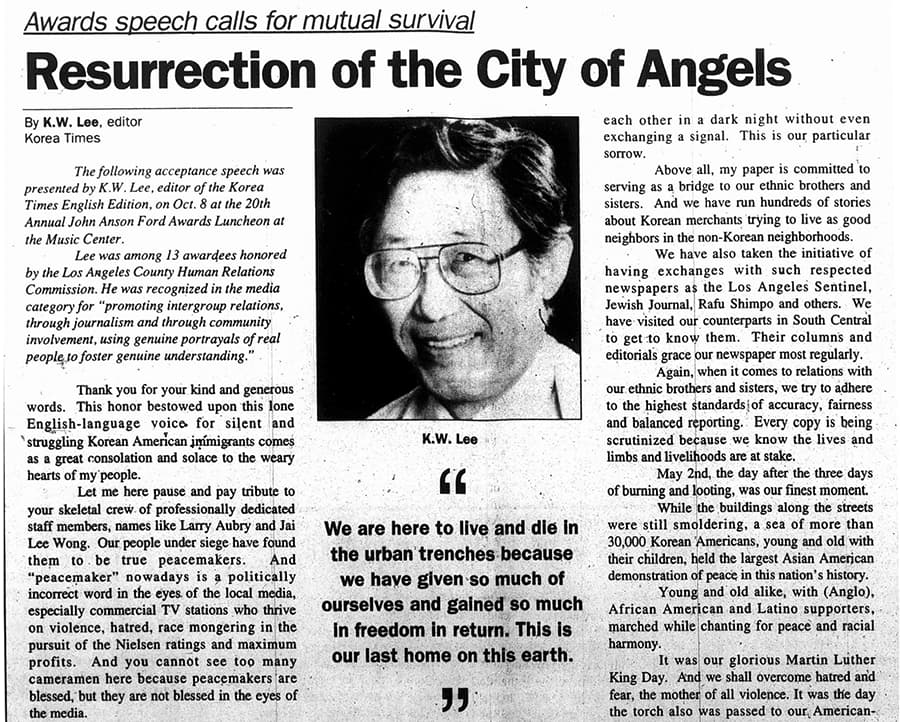

K.W. Lee is one of 13 individuals honored by the L.A. County Human Relations Commission. He was recognized for “promoting intergroup relations, through journalism and through community involvement, using genuine portrayals of real people to foster genuine understanding.

Community Coalition, a Black and Latino non-profit organization, leads efforts in South Central to block the rebuilding of liquor stores in the area. Local residents claimed that liquor stores were a detriment to public health in South Central.

The City of Los Angeles imposes restrictions on the rebuilding of liquor stores in South Central to address public health concerns believed to be caused by the high density of liquor stores in the neighborhood.

Korean American business owners file suit against the City of Los Angeles for restrictive policies on the rebuilding of their businesses in Korean American Legal Advocacy Fund v. City of Los Angeles.

Korean Youth and Community Center, the Korean Immigrant Workers Advocates, and the UCLA Asian American Studies Center hosted the first National Korean American Studies Conference to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the Los Angeles Civil Unrest of 1992. K.W. Lee delivers the keynote address.

President Clinton announces One America in the 21st Century: The President’s Initiative on Race. Angela Oh, a prominent Korean American lawyer who was active during Sa I Gu/Civil Unrest, is the sole Asian American member.

The K.W. Lee Center for Leadership is founded to provide “youth with the tools and opportunities necessary to become future leaders. The Center offers youth leadership training and educational programs that encourage community organizing. The mission of the Center is to teach and train youth to take proactive steps towards improving and enriching the quality of life in their communities.”

UCLA Asian American Studies Center’s Amerasia Journal publishes Los Angeles Since 1992: Commemorating the 20th Anniversary of the Uprising a collection of articles and writings reflecting on the legacies and impact of the L.A. Uprising.

Lee, K.W., “The Fire Next Time?: Ten Haunting Questions Cry Out for Answers and Redress,” Amerasia Journal 38, no. 1 (2012): 84-90. ![]()