Never Forget

Filipinx Americans and the Philippines Anti-Martial Law Movement

Never Forget > Essay

ESSAY

Never Forget

Digital Exhibition Essay

By Josen Diaz and Joy Sales

Exhibition Curators

On February 25, 1986, with U.S. military assistance, Ferdinand Marcos and his family fled the presidential palace in Malacañang for Andersen Air Force Base in Guam and then to Hickam Air Force Base in Hawai’i, where he remained until his death in 1989. For four days that February, a mass movement in the Philippines toppled the dictator. While People Power, as it would come to be known, took shape as a unified gathering along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA), it was comprised of an array of different groups and organizations both in the Philippines and outside of the country, many of which began their work well before and would continue it well after the dictator’s ousting.

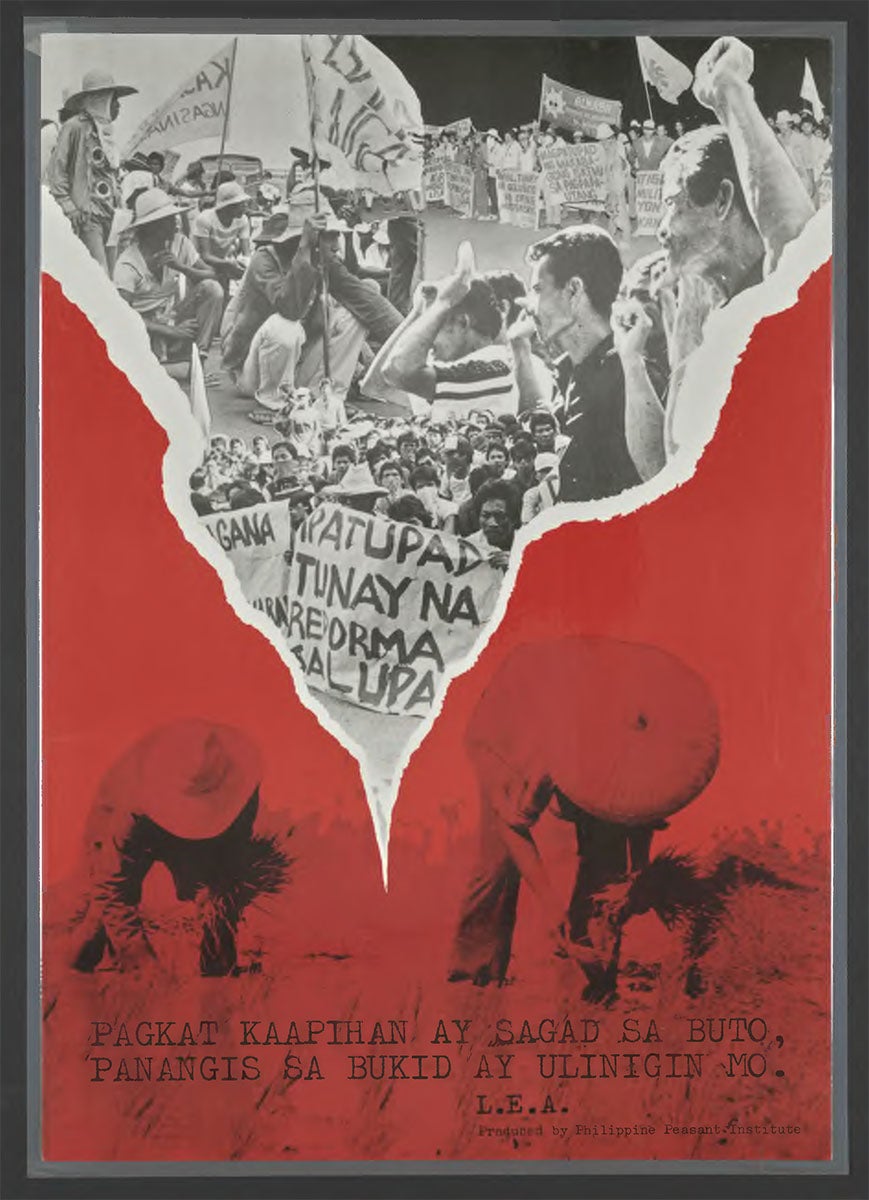

The posters that comprise this collection are among the materials donated by former anti-martial law movement (AMLM) activists from their personal collections. They reflect the strength of the movement as well as the depth of the organizing that made it. Activists Madge Bello and Vince Reyes acknowledged anti-martial law and anti-Marcos political work in the U.S. as “‘keeping the light of resistance’ aflame” by maintaining the flow of information to and from the Philippines and to the American public, especially in the early years of martial law when repression in the Philippines silenced democratic forces.1

The movement for a genuinely sovereign and democratic Philippines precedes Marcos’s presidency and has been intertwined with U.S. colonial and neocolonial policies. During the Philippine-American War, U.S. officials set up prison and policing systems and passed sedition laws that allowed for the execution, imprisonment, and exile of nationalist leaders. In the 1930s, many labor activists were forced underground when the U.S. colonial government outlawed the Communist Party (1932) and when martial law was written into the Constitution when the Philippines was a U.S. commonwealth (1935). Despite these counterrevolutionary efforts, nationalism arose in grassroots forms and among traditional politicians. The guerrilla movement of peasants in Luzon, the Hukbalahap, waged agrarian revolution during World War II. Claro Recto, a statesman who held elected and appointed positions throughout his career as a politician, advocated for “Filipino first” policies in the 1950s. The presence of seemingly “anti-American” politics in the Philippines made way for U.S. support for the Marcos presidency and his declaration of martial law.

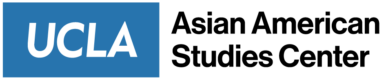

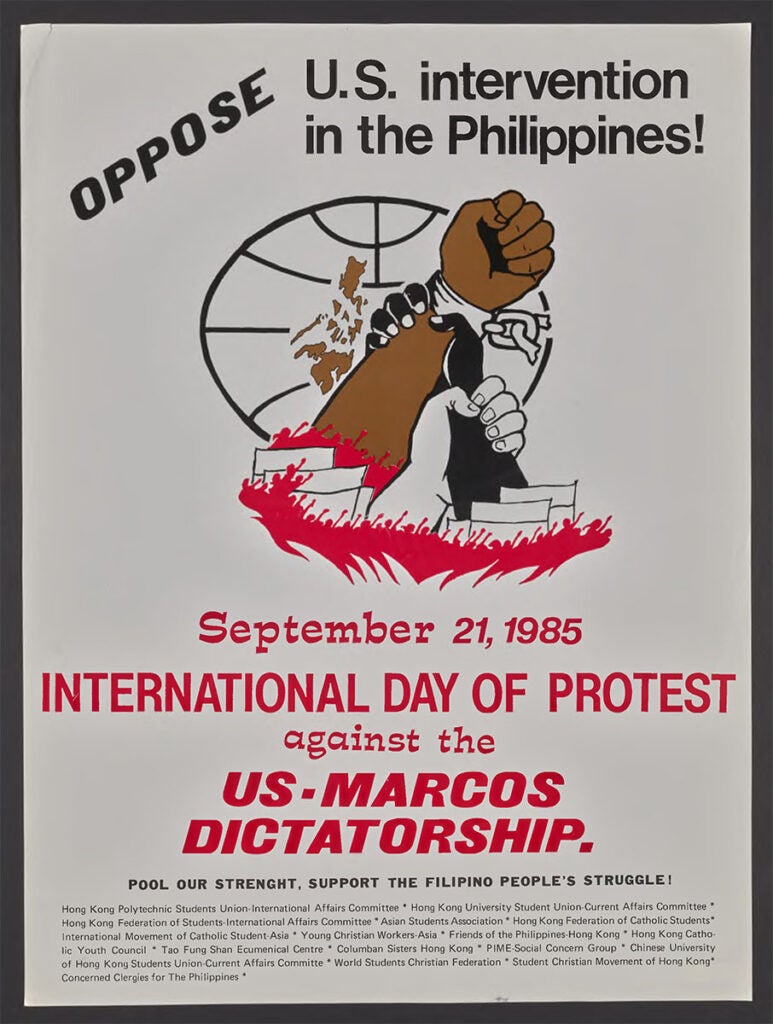

Ferdinand Marcos was elected as the 10th president of the Republic of the Philippines and assumed office in 1965. While he ran on a campaign that touted his fabricated military heroism and promises to change Philippine politics, much of his presidency focused on funneling money to his family and cronies, rewarding his political allies, and punishing his critics and enemies. Under Marcos’s presidency, the national debt increased, and poverty intensified. The United States government was a strong supporter of the administration, and Philippine-U.S. collaborations made the Philippines a significant site of U.S. strategic military operation throughout Marcos’s tenure [ view poster ].

By the early 1970s, political unrest became a key feature of Marcos’s tenure. The First Quarter Storm was a period of rebellion and resistance in the first quarter of 1970 organized by students, workers, and poor communities. They protested the growing corruption under the increasingly authoritarian government. This resistance was met with brutal force by the police, and the Battle of Mendiola was the most violent night of the First Quarter Storm. Many First Quarter Storm activists were members of national democratic organizations, such as Kabataang Makabayan (KM) and MAKIBAKA. Kabataang Makabayan was an anti-imperialist youth and student organization founded in 1964, and MAKIBAKA, a women’s liberation organization, was founded in 1970 [ view poster ].

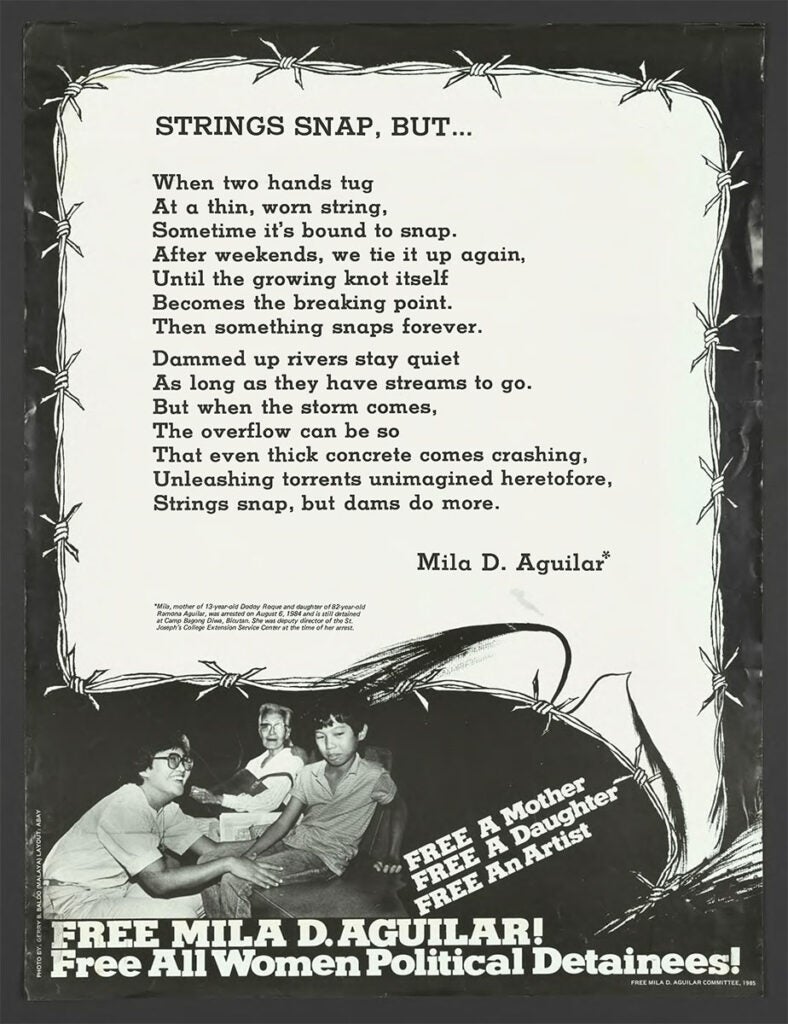

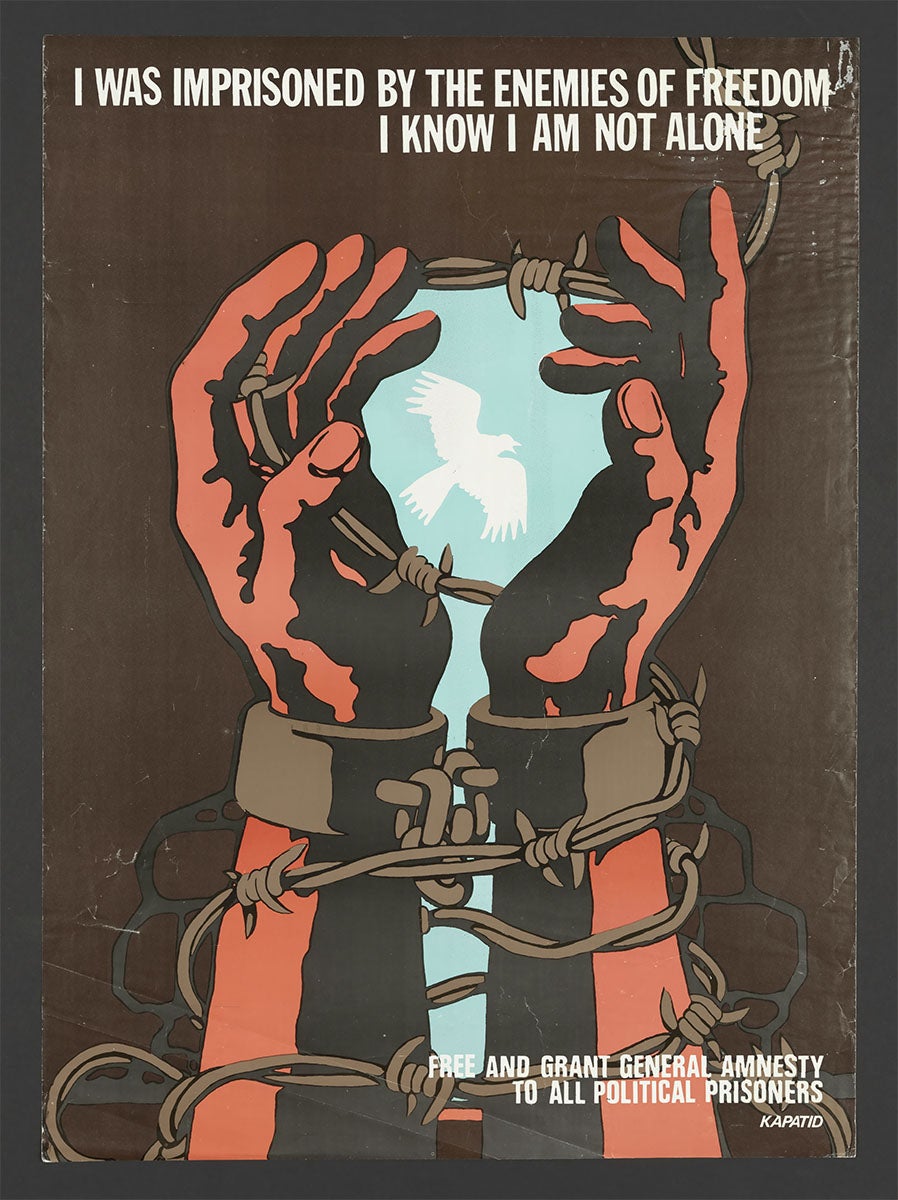

Citing the insurrection of the First Quarter Storm and the radicalism of leftist groups in the country, Marcos declared martial law in 1972. With martial law, he suspended the writ of habeas corpus, enforced curfews, and censored the press. Under martial law, activists were subject to torture, disappearance, and death. The Marcos regime was responsible for numerous human rights violations. Several of the posters feature the militant activists who were disappeared during the martial law era, including Bernabe Buscayno, Mila Aguilar, and Rolando Olalia [ view posters ]. Several of these activists were part of, affiliated with, or were said to be connected to the Communist Party of the Philippines and the New People’s Army, both of which waged fierce struggles against the regime [ view poster ]. Kapatid was established in 1978 as a support group for families and friends of political prisoners. The poster notes that detention serves as a brutal tactic of authoritarian power over the world [ view poster ]. Campaigns to free political prisoners drew global support and helped de-legitimize the Marcos regime.

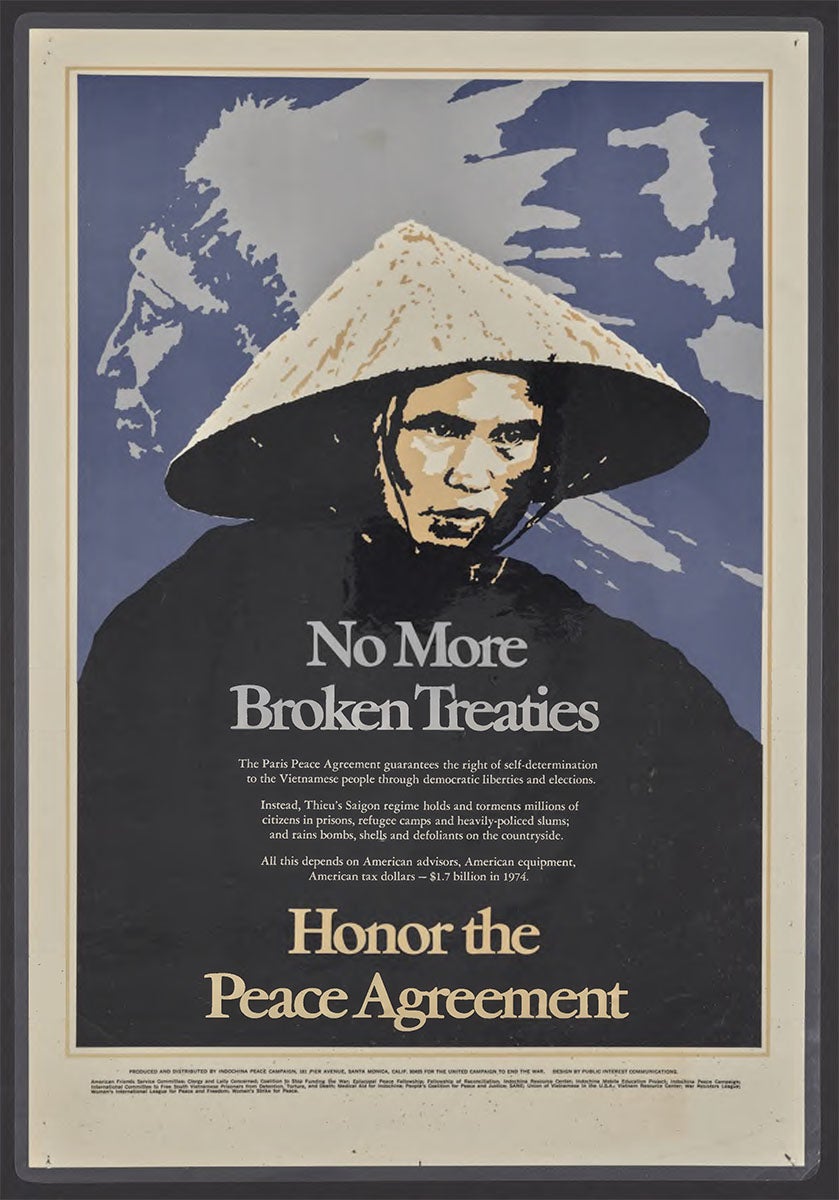

Marcos took office at the height of the U.S. war in Vietnam. Military bases throughout the Philippines and those in Hawai’i, Guam, and Okinawa operated as critical sites for U.S. defense operations in Asia. Marcos sent the Philippine Civic Action Group (Philcag) as a non-combatant military unit to Vietnam. His political support for the U.S. war continued when the war was becoming increasingly unpopular both in the United States and the Philippines. Several of the posters in this collection call attention to U.S. support of the Marcos regime as well as the ways that the regime allowed U.S. imperialist policies to take hold over the Philippines. For instance, one poster features the Indochina Peace Campaign, an antiwar project that began in 1972, the year Marcos declared martial law, and was organized to coordinate regional resistance against the war [ view poster ]. Activists worldwide pointed to the war as an assault against Vietnamese self-determination and a continuation of the long history of colonialism and imperialism. In the Philippines, organizers made important connections between U.S. policies in the Philippines and the ongoing war in Vietnam. In 1983, Marcos signed an extension of the U.S. lease on the military bases, which had anchored U.S. military presence in the region for most of the 20th century.

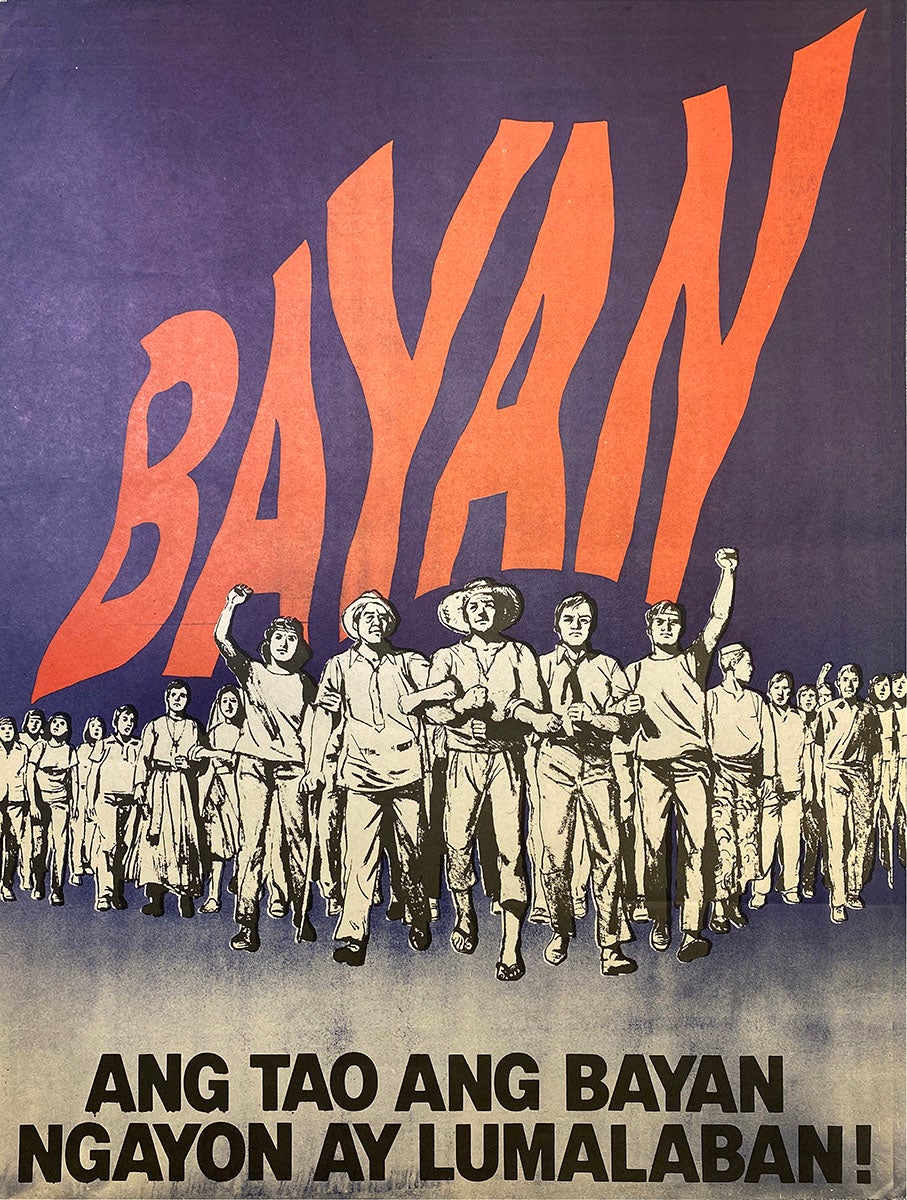

Labor unions and organizations were some of the most vociferous opponents of the regime, and the regime often worked to stifle the power of unions and silence labor leaders. Kilusang Mayo Uno (May First Movement; KMU) was established in 1980 as an organization focused on building collective power among workers to stand up for their labor and human rights. While KMU was attentive to issues specific to Filipinx workers, it was also part of a larger labor movement that was global in scope [ view poster ].

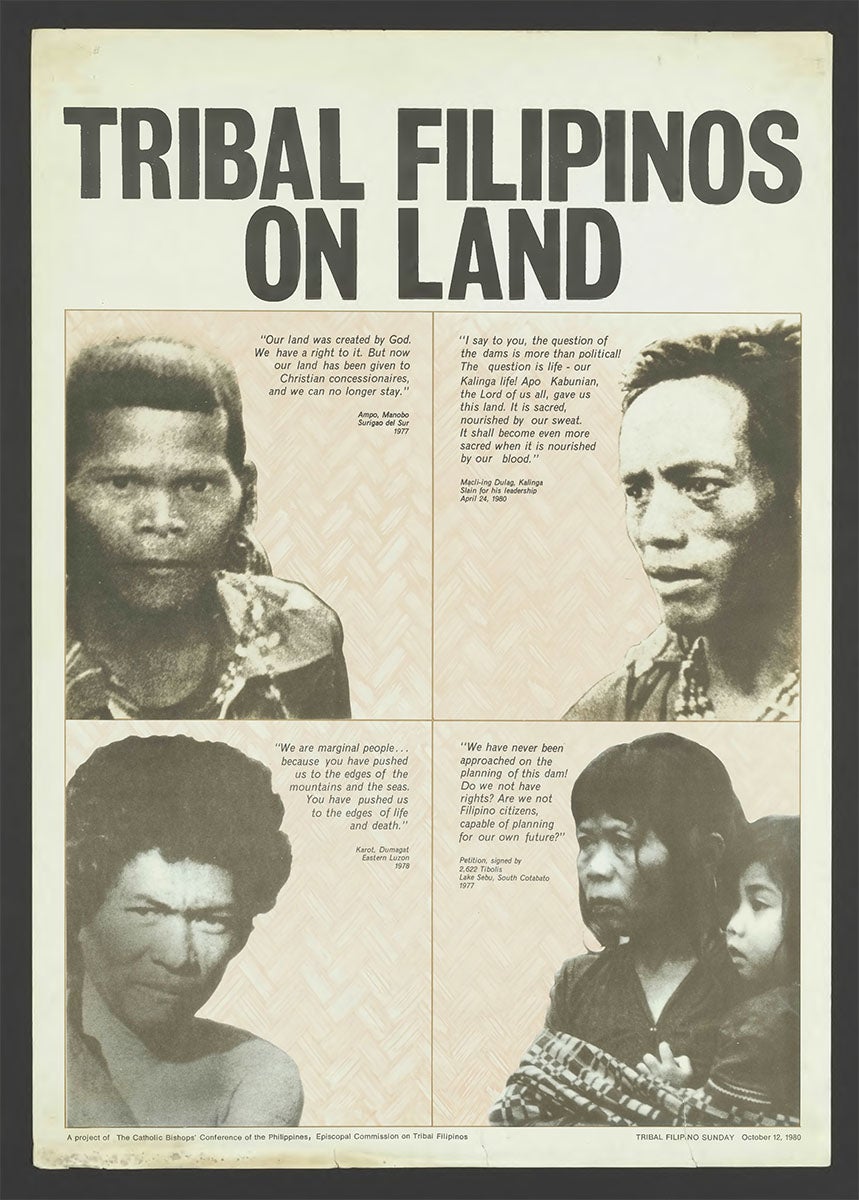

The Marcos family was often at odds with the Catholic Church in the Philippines, a strong force in Philippine politics. In 1975, the church organized the Alay Kapwa program to emphasize sacrifice on behalf of the poor and their suffering [ view poster ]. By the 1980s, the church highlighted issues that affected particular communities in the country under the Marcos government. The Episcopal Commission on Tribal Filipinos, organized by Catholic bishops, attempted to bring awareness to issues affecting Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines [ view poster ]. Under the Marcos presidency, Marcos and his cronies deployed land-grabbing tactics and programs that dispossessed Indigenous peoples [ view poster ].

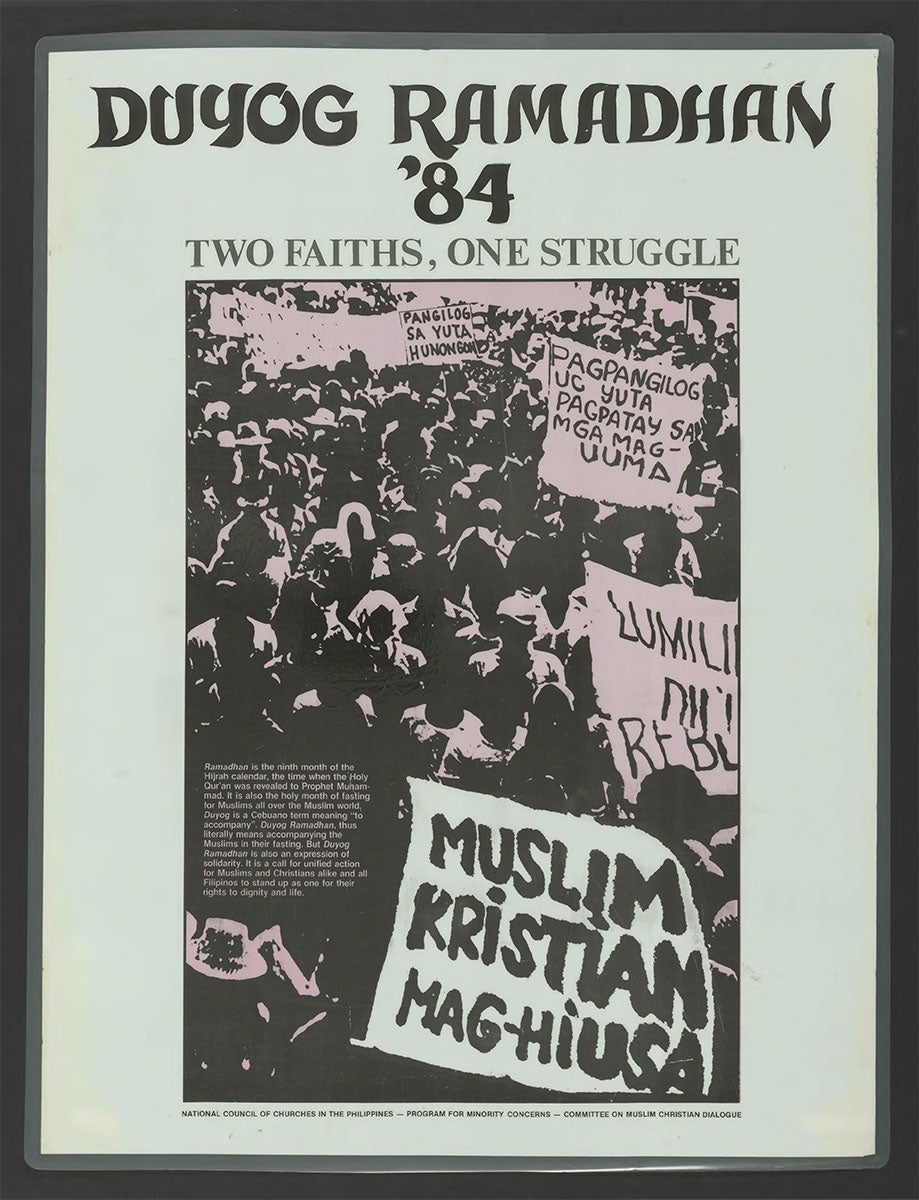

In the first several years of martial law, Marcos deployed the Philippine military in the southern Philippines to wage a bloody battle against Muslim “separatists.” It resulted in thousands of people dead and even more displaced. Duyog Ramadan was a solidarity iftar between Muslims and Christians to reflect a shared struggle for self-determination [ view poster ]. Iftar is the gathering around a meal at the break of fast at sunset during Ramadan and is a time for reflection and building communal relationships.

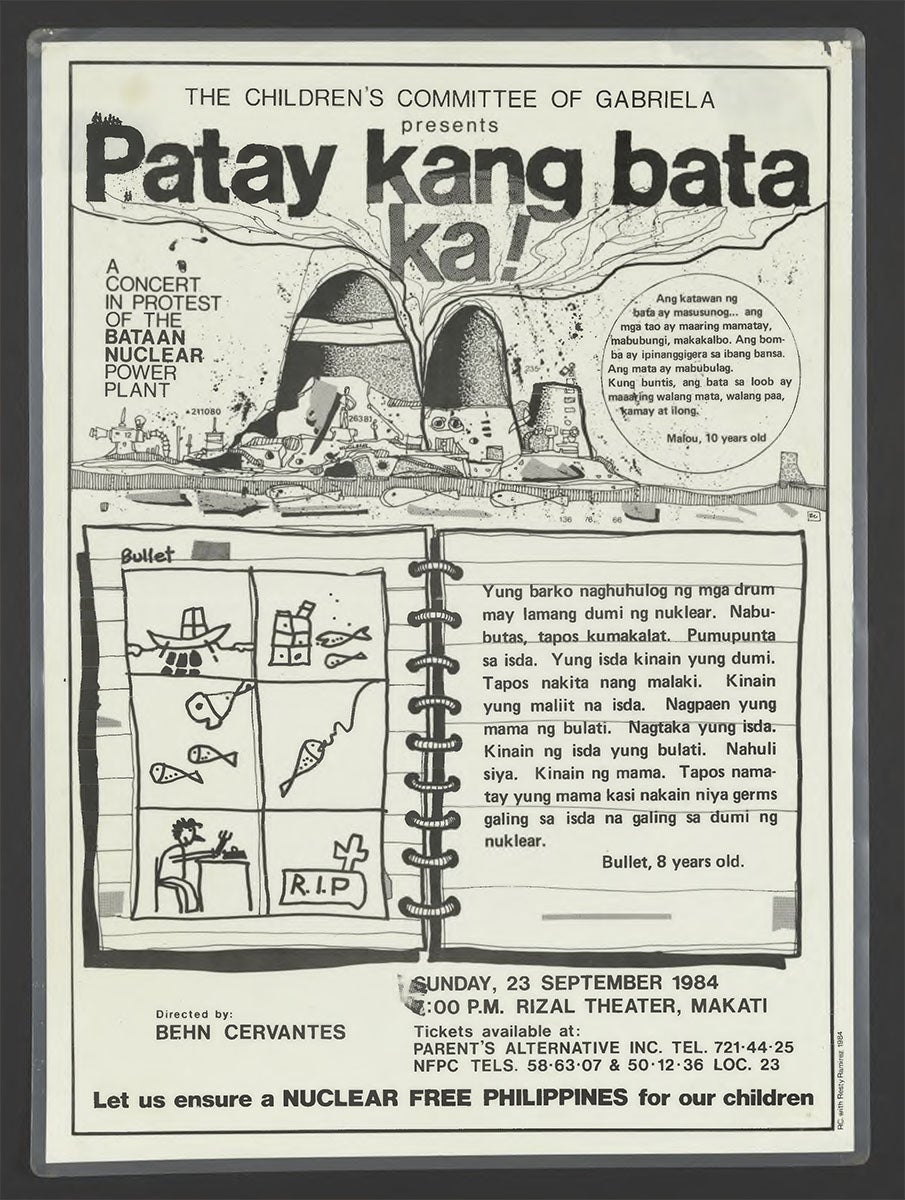

Near what would be the end of his presidential term, Marcos ordered the construction of the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant. The plant was a clear example of the president’s political and financial dealings with multinational corporations and how such projects put Filipinx people in harm’s way. The poster depicts a concert organized by the GABRIELA to call attention to the plant and its harmful effects on children [ view poster ]. GABRIELA formed in the 1980s as a women’s coalition that linked women’s empowerment to issues like land and labor rights and public health [ view poster ]. The figure of the child became an important symbol for activists and organizers. Another poster depicts Joel Abong, a starving child who suffered the devastating effects of the Negros famine, a direct result of the sugar crisis that followed the regime’s economic policies [ view poster ].

For the regime, culture became a key avenue for displaying and symbolizing its power. Cultural producers, in turn, became crucial participants in anti-martial law activism. Writers, musicians, painters, and performers created important critiques against the dictatorship. Moreover, culture became a way for people outside the Philippines to call attention to the issues facing Filipinxs in the Philippines. In 1984, musicians and other artists organized a series of Filipino music concerts in the Netherlands [ view poster ]. The music focused on the social and political realities of the Filipinx masses under martial law.

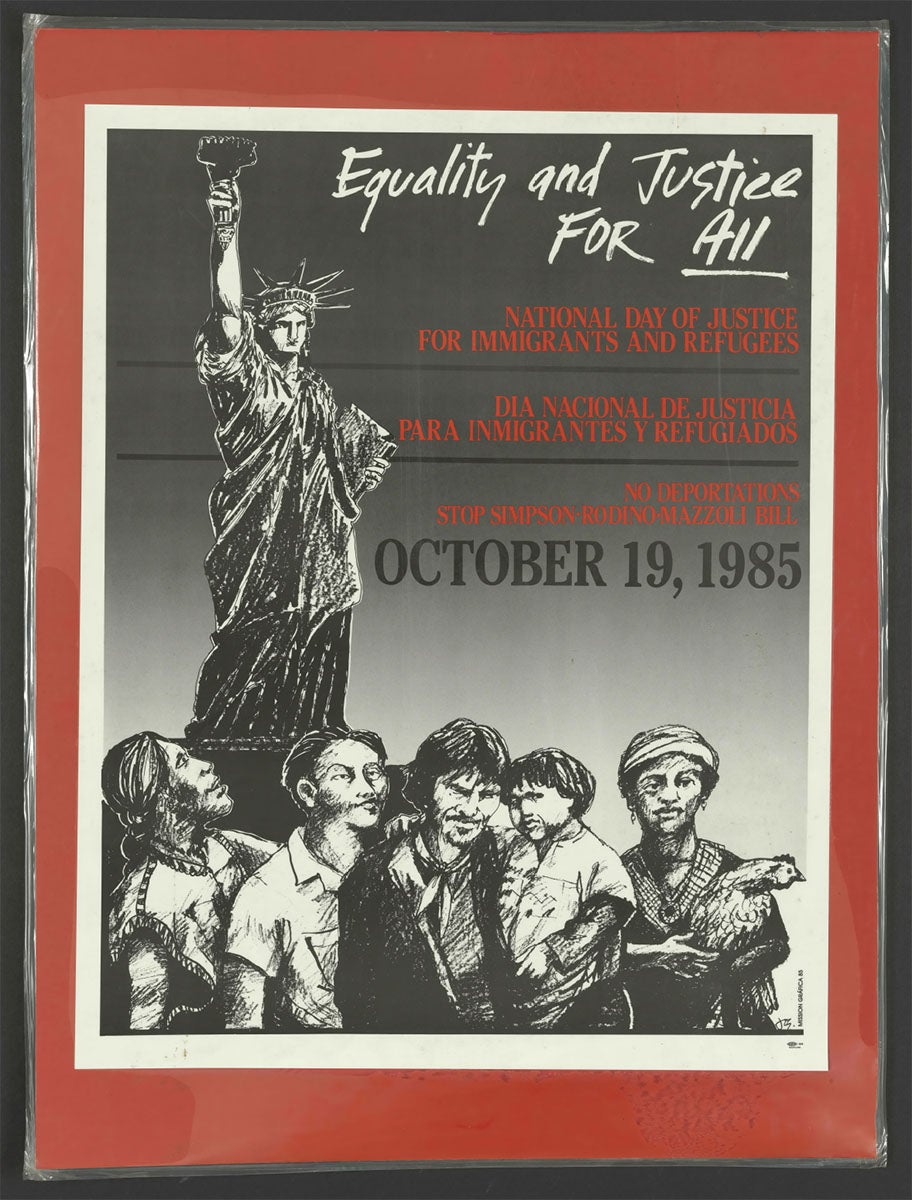

Within a year of martial law’s declaration, activists in the United States formed organizations such as the National Coalition to Restore Civil Liberties in the Philippines, Katipunan ng Demokratikong Pilipino (KDP), Movement for a Free Philippines, and Friends of the Filipino People. Diasporic Filipinxs and their allies made up the transnational component of the anti-martial law movement and conducted political education and campaigns that exposed human rights abuses and criticized U.S. support for martial law.

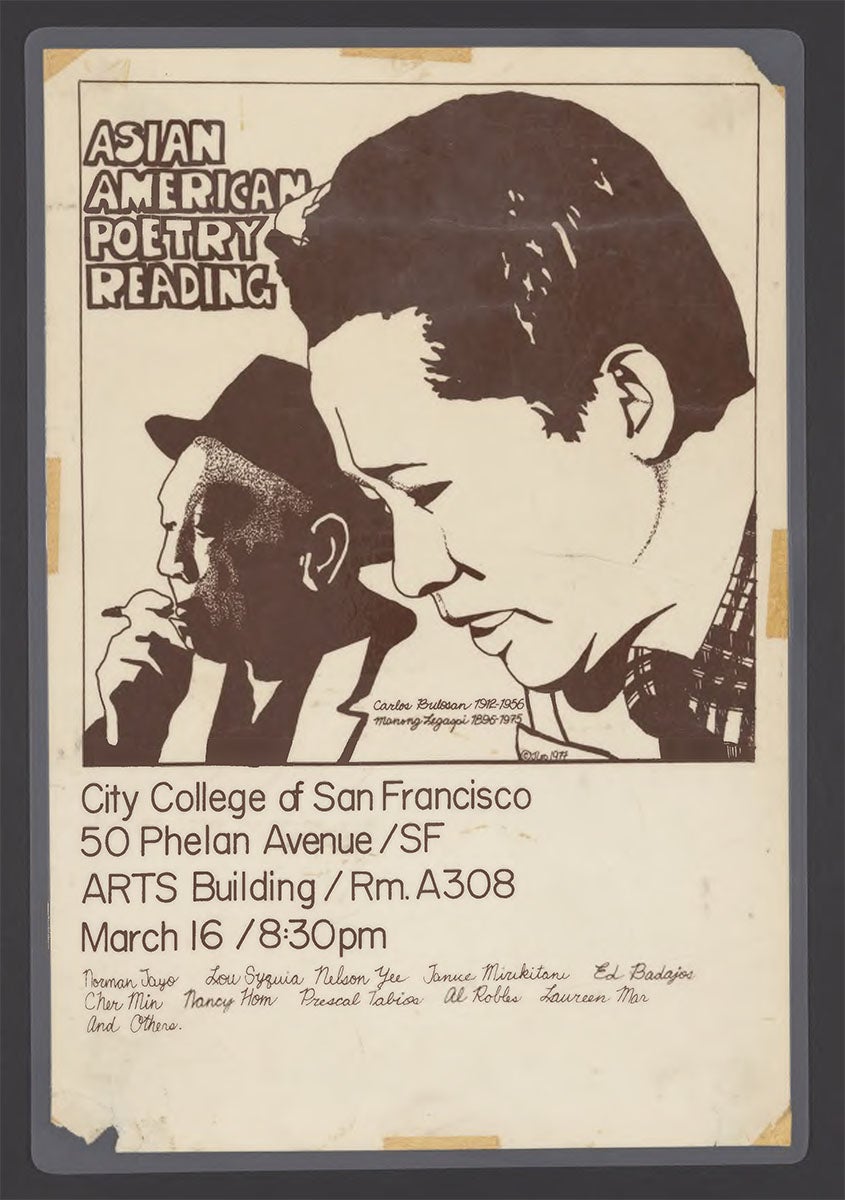

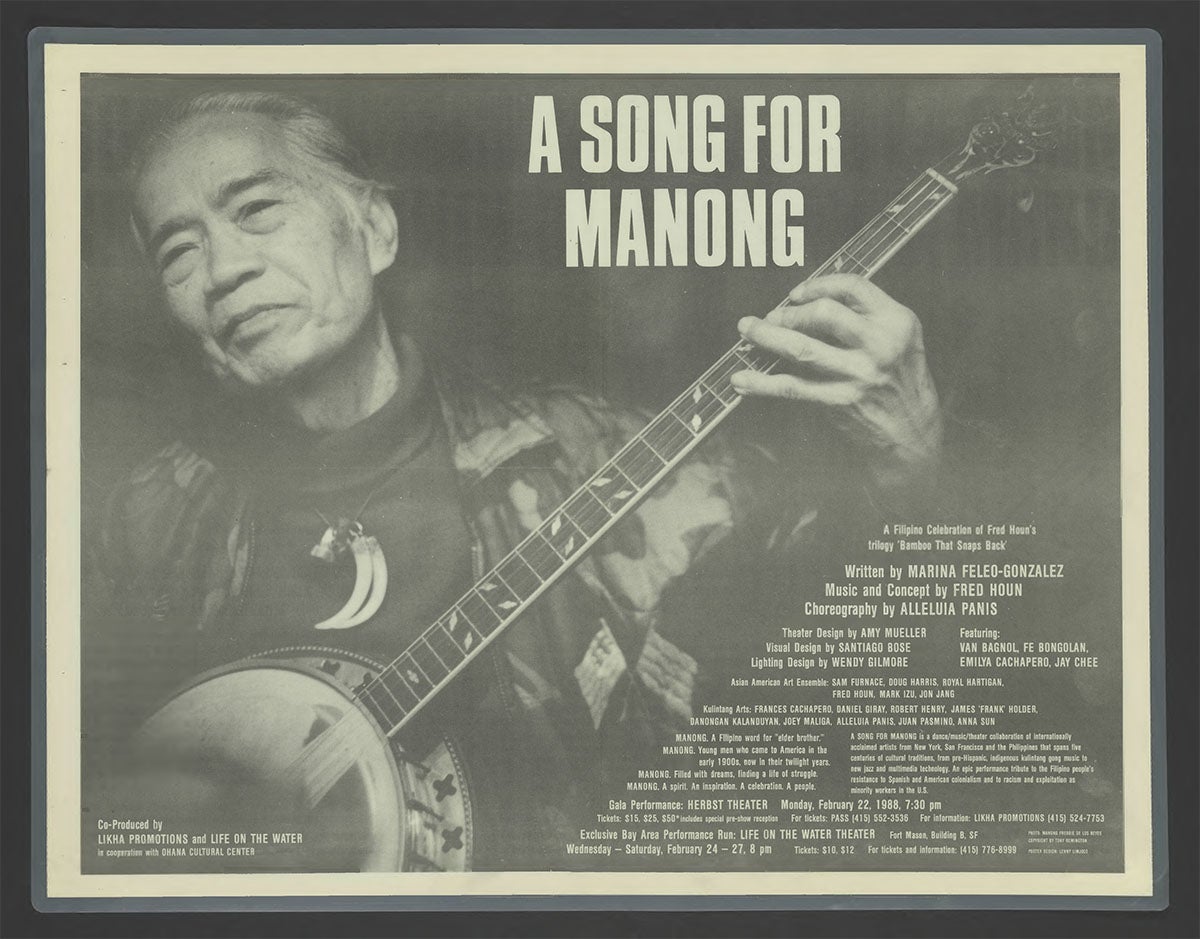

Filipinx Americans and other Asian American groups in the United States used culture to connect issues in the United States to those in the Philippines [ view poster ]. With Asian Arts Ensemble and Kulintang Arts, Fred Ho created A Song for Manong as a musical tribute to the struggles of Filipinx immigrant laborers in the United States [ view poster ]. Throughout the 1970s, the manong generation of postwar agricultural and service workers met increasing marginalization and discrimination. The I-Hotel movement in San Francisco strived to maintain housing security for a generation of Filipinx workers amidst urban redevelopment and gentrification. KDP and other organizations showed how racial and class discrimination in the United States was part of the long legacy of U.S. colonialism and imperialism in the Philippines2 [ view poster ].

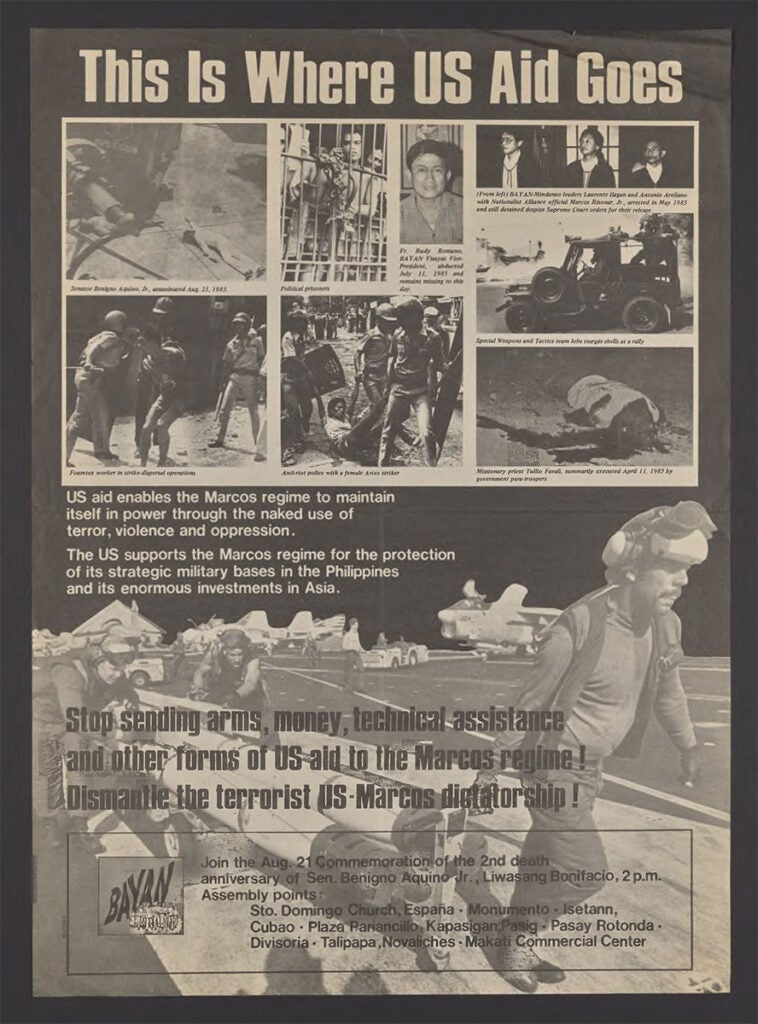

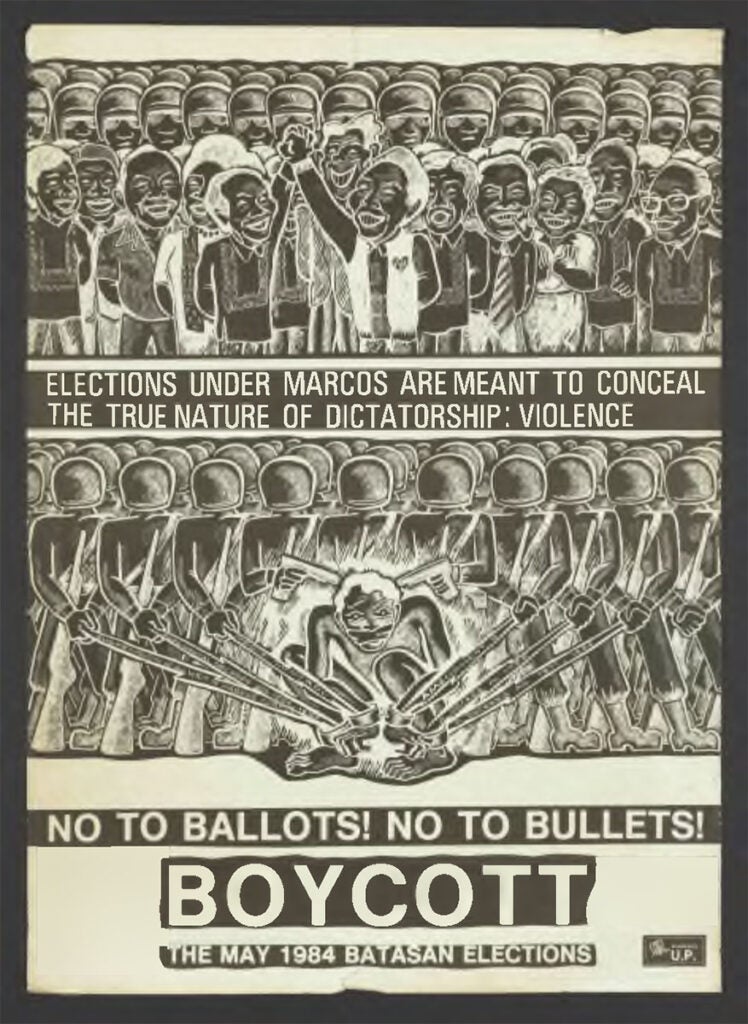

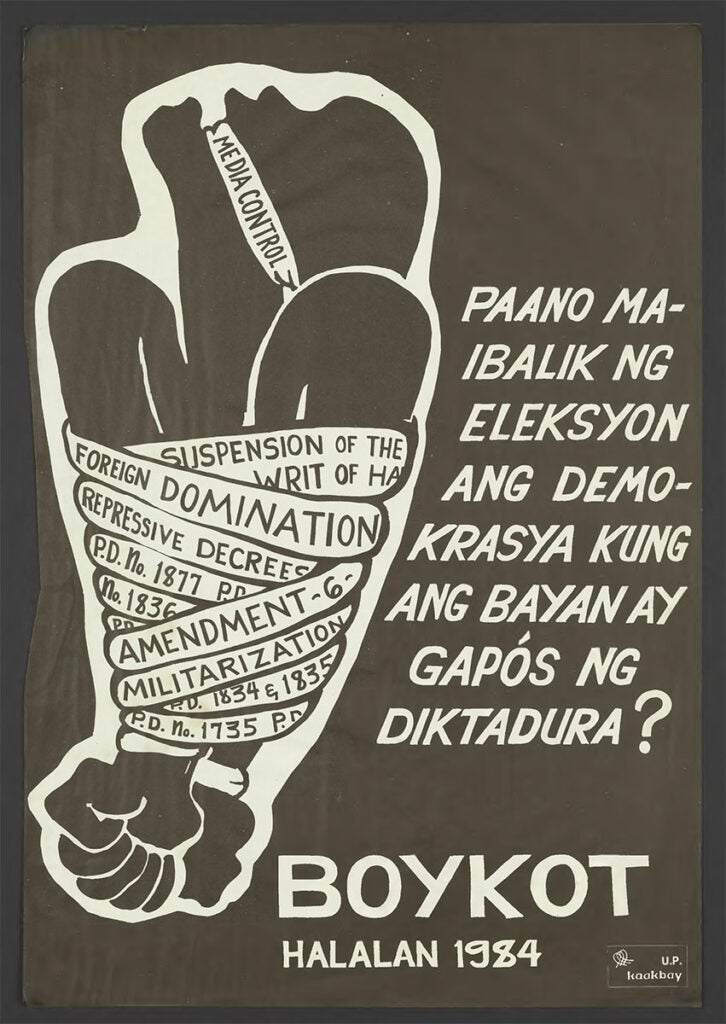

Marcos eventually lifted martial law in 1981, but many activists viewed this as the end of martial law in name but not in practice. However, the paper lifting of martial law allowed for the formation of alliances like BAYAN and GABRIELA that could now legally protest Marcos [ view poster ]. Kaakbay UP was a political organization that formed at the University of Philippines, Diliman. In 1984, the students called for a boycott of the 1984 presidential elections, arguing that it was a presidential tactic to paint a picture of democracy in the country while the administration consistently violated democratic principles [ view posters ].

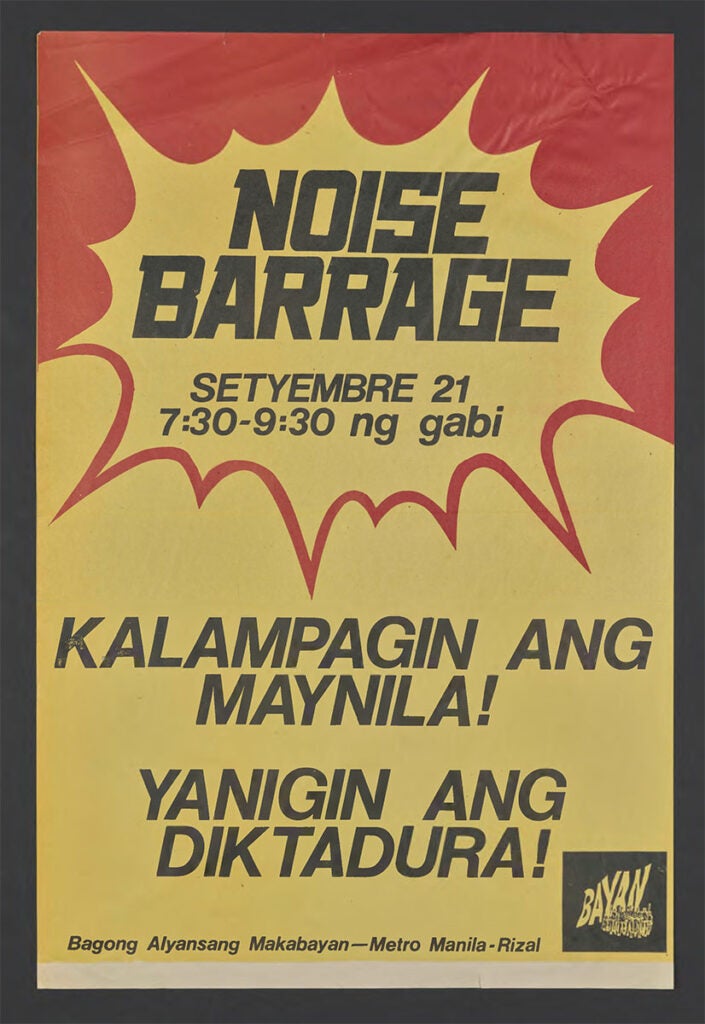

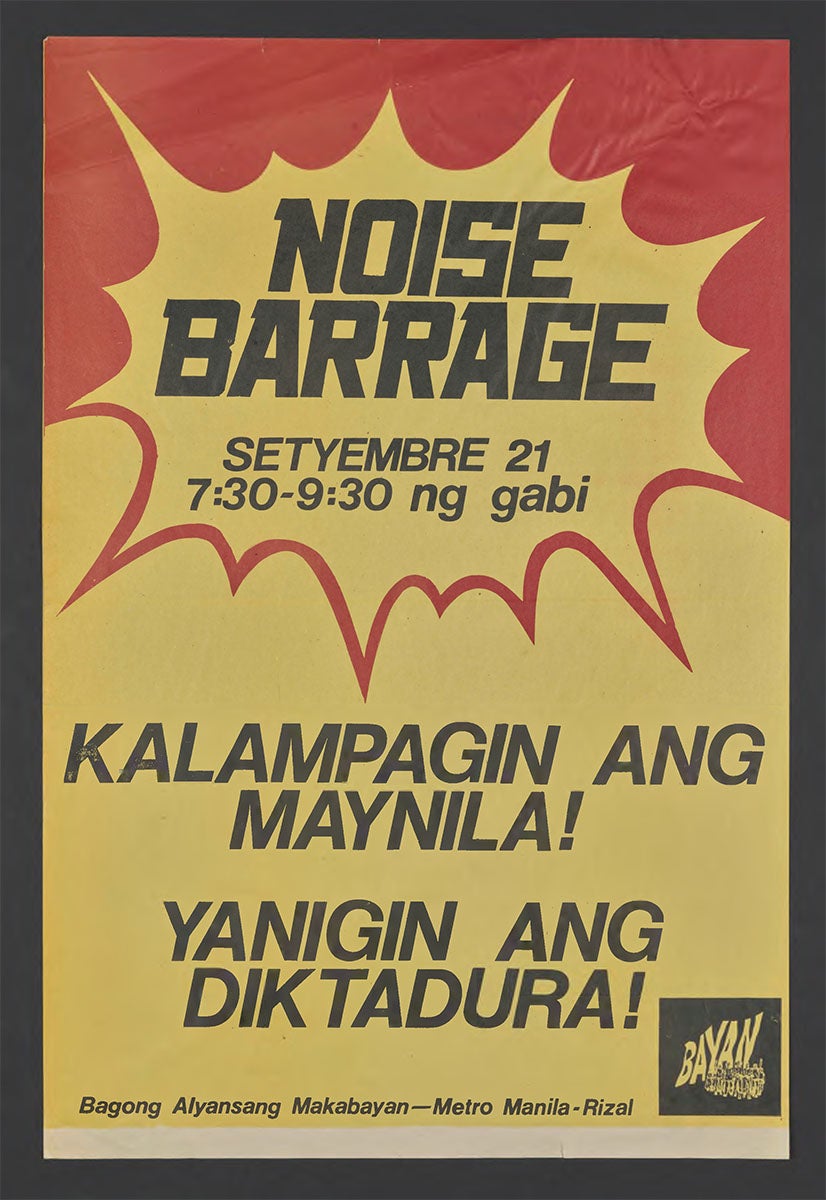

People in the Philippines, the United States, and all over the world continue to recognize September 21 as the anniversary of the declaration of martial law [ view posters ]. Anti-martial law commemorations and demonstrations take the form of protest and performance. Noise barrages gained popularity during the martial law period as a form of nonviolent protest to demonstrate the people’s opposition to the dictatorship, and they have continued against the Duterte and the second Marcos presidencies [ view poster ].

In 2022, Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., the son of the dictator, was elected to the Philippine presidency. Much of his campaign was built around historical revisionism, or the attempt to revise the details and facts of history. He claimed that the martial law period was a golden age of Philippine history, one of modernization and progress. The posters of this collection are evidence of that falsity, a reminder of the importance to never forget.3 Anti-martial law activists believe that the anti-martial law movement must continue because the conditions of martial law persist. The movement, then and now, has the power to topple a dictator.

1 74. Bello, Madge and Vincent Reyes. “Filipino Americans and the Marcos Overthrow: The Transformation of Political Consciousness” Amerasia 13.1 (1986-87): 73-83.

2 See Kim Geron, Enrique de la Cruz, Leland T. Saito and Jaideep Singh’s “Asian Pacific Americans’ Social Movements and Interest Groups” [Political Science and Politics 34.3 (2001): 618-24].

3 See Joy Sales’s “#NeverAgainToMartialLaw: Transnational Filipino American Activism in the Shadow of Marcos and Age of Duterte” [Amerasia 45.3 (2019)].