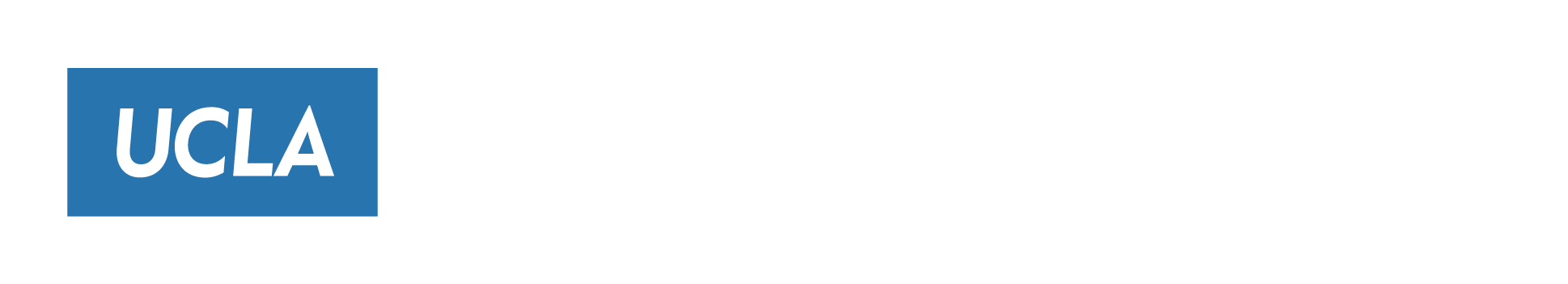

Yuri Kochiyama at Central Park anti-war demonstration, c. 1968. Photo Credits

YURI KOCHIYAMA

Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014) is one of the most distinguished Asian American activists of the 20th century. She is best known for her work promoting Afro-Asian solidarity.

Her experiences living in US concentration camps during World War II gradually shaped her social consciousness. During the 1950s, she supported Asian American issues and followed the events of the emerging Civil Rights Movement. In 1960, Yuri, her husband, and six children moved to Harlem. There Yuri got involved in the Black movement and met Malcolm X.

Remember that consciousness is power. Consciousness is education and knowledge. Consciousness is becoming aware. It is the perfect vehicle for students. Consciousness-raising is pertinent for power, and be sure that power will not be abusively used, but used for building trust and goodwill domestically and internationally. Tomorrow’s world is yours to build.

-Yuri Kochiyama-

Mary Yuri Nakahara was born on May 19, 1921, in San Pedro, CA, the child of immigrants from Japan. Her father, Seiichi Nakahara, was a fishmerchant entrepreneur with social connections to the Japanese elite, and her mother, Tsuyako “Tsuma” (Sawaguchi) Nakahara, was a college-educated homemaker and occasional piano teacher.

The Nakahara family at their San Pedro home, circa 1924. Tsuya (left) and Seiichi (right) with children Yuri, Pete and Arthur. Photo Credits

The Nakahara family at their San Pedro home, circa 1924. Tsuya (left) and Seiichi (right) with children Yuri, Pete and Arthur. Photo Credits

She grew up with her older brother, Art, and her twin brother, Pete. They were part of the “Nisei” generation, or children of Japanese immigrants.

Despite their middle-class comforts, her family experienced residential segregation and other forms of racism. Anti-Japanese racism was widespread even before World War II.

Growing up, Yuri was actively involved in community service and extracurricular activities. This was a time when racism excluded the participation of most Nisei in mainstream organizations.

When she later gained an awareness of racism, these experiences would have an impact on her.

Yuri graduated from San Pedro High School in 1939 and Compton Junior College, with a major in journalism and minor in art, in 1941.

The Nakahara family in their San Pedro home, 1938. (From left) Arthur, Seiichi, Peter (standing), Yuri, and Tsuya. Photo Credits

The Nakahara family in their San Pedro home, 1938. (From left) Arthur, Seiichi, Peter (standing), Yuri, and Tsuya. Photo Credits

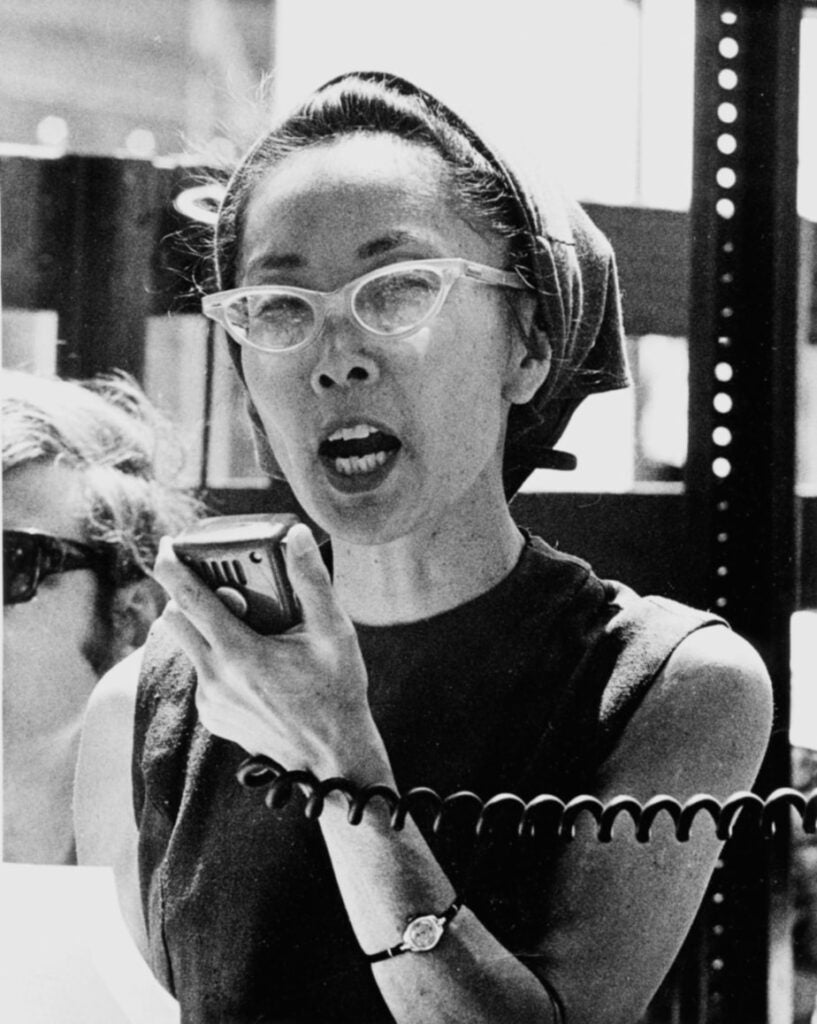

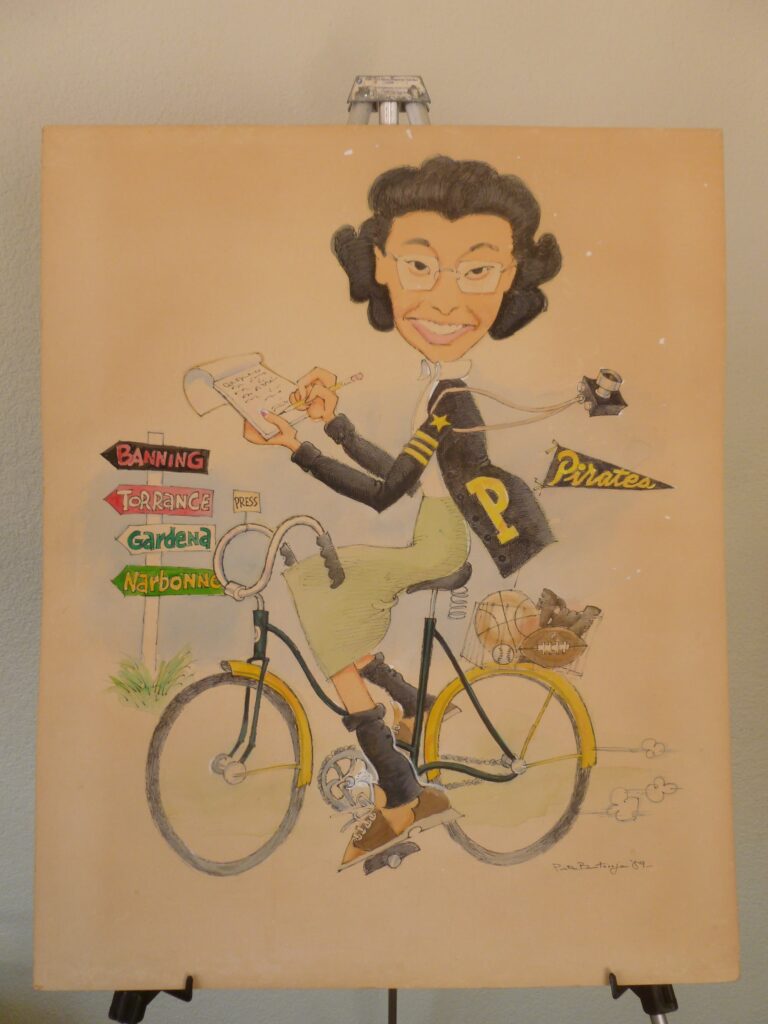

This caricature depicts Yuri’s numerous travels by bicycle to cover San Pedro High School sporting events for the San Pedro News-Pilot. Artist, Peter Bentovoja. Courtesy of Norma L. Brutti. Source: Heartbeat of Struggle. Photo Credits

Growing up, Yuri was actively involved in community service and extracurricular activities. This was a time when racism excluded the participation of most Nisei in mainstream organizations.

When she later gained an awareness of racism, these experiences would have an impact on her.

Yuri graduated from San Pedro High School in 1939 and Compton Junior College, with a major in journalism and minor in art, in 1941.

This caricature depicts Yuri’s numerous travels by bicycle to cover San Pedro High School sporting events for the San Pedro News-Pilot. Artist, Peter Bentovoja. Courtesy of Norma L. Brutti. Source: Heartbeat of Struggle. Photo Credits

Yuri’s life changed dramatically on December 7, 1941. That same day, the FBI came to arrest her father and about 1,300 other Japanese Americans. Nobody knew where these men were taken or what would happen to them.

While the US claimed that those arrested were threats to national security, this was not true. Instead those arrested tended to be community leaders or businessmen with connections to Japan.

Yuri’s father had recently had ulcer surgery when the FBI agents took him away.

His health greatly deteriorated during his six weeks in detention. The government released him only when he was near death. Mr. Nakahara died the next day, on January 21, 1942, at his family home. He was 54 years old.

Seiichi Nakahara and Tsuya Sawaguchi’s wedding picture, 1917. Photo Credits

The problems for Japanese Americans did not begin with Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor. As early as 1900, an anti-Japanese movement began to grow. This included White supremacists wanting to “Keep California White.”

There were many laws that discriminated against Japanese Americans, including the Alien Land Act of 1913 barring Japanese Americans from purchasing land and the Immigration Act of 1924 banning immigration from Japan.

Yuri too experienced anti-Japanese racism. She couldn’t believe that people began to see her as suspect, this in her hometown where she seemed to have been so accepted.

Yuri’s twin brother, Pete, decided he wanted to join the US Army. It was a confusing time, with Mr. Nakahara accused of being a danger to national security, while his son was allowed to serve in the US Armed Forces.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. In the Spring of 1942, the US military began posting “evacuation notices,” giving one week’s notice to all Japanese American families in California and parts of Washington, Oregon, and Arizona.

Yuri, her brother Art and her mother, like the other 110,000 Japanese Americans, had to pack their belongings and prepare to leave. They were allowed to take only what they could carry. Yuri was 20 years old

Yuri and her family were sent to the Santa Anita “assembly center.” The conditions were harsh. Their new “home” smelled like the horses that had just recently lived there. They were forbidden from leaving.

Yuri stayed active, in part as a way to cope. She continued to teach Sunday School and also worked as a nurse’s aid for a meager $8 a month.

After seven months, Yuri and her family were moved to Jerome, Arkansas, one of the ten more permanent concentration camps.

In Santa Anita, and continuing in Jerome, Yuri transformed her Sunday School class into a letter writing campaign to support Japanese Americans in the US military.

The Crusaders, as they named themselves, were soon writing to hundreds of soldiers as well as to Japanese American orphans and tuberculosis patients.

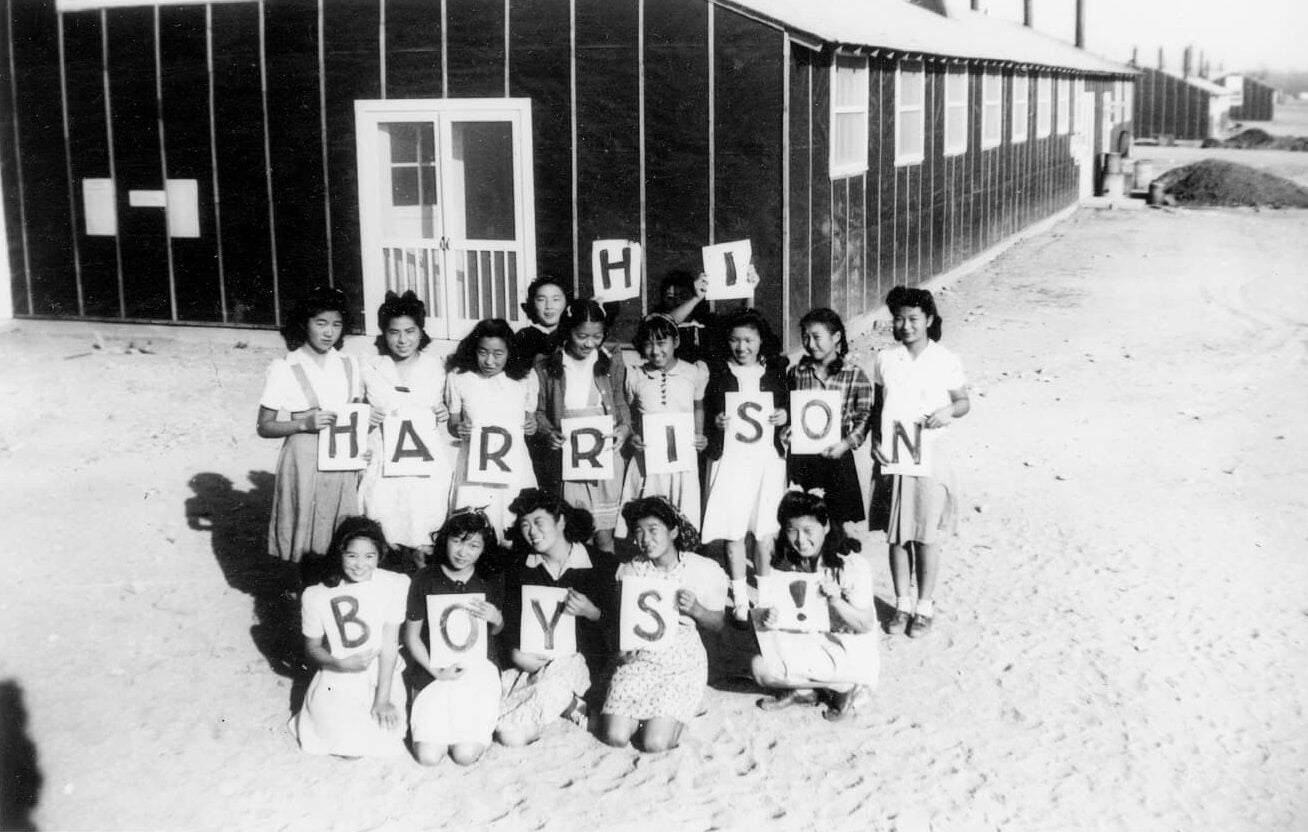

The Junior Crusaders at Jerome AK internment camp, welcoming Nisei GI’s visiting from Fort Harrison, Indiana (circa 1944). Photograph taken by one of the Fort Harrison Nisei soldiers. Photo Credits

Yuri’s mom (kneeling, second from right) with Senior Crusaders. Jerome, Arkansas internment camp, circa 1944. Photo Credits

In Jerome, Yuri printed excerpts from soldiers’ letters in her Jerome camp newspaper column, “Nisei in Khaki.”

This letter is from a Nisei soldier stationed in Italy, written to Mrs. Nakahara in the Jerome concentration camp. He affectionally calls her “mom.” Mrs. Nakahara actively supported the young women in their letter writing to Nisei soldiers.

Bill in uniform, France 1944. “To my darling Mary.. With only love.. Always.. Your Bill” Photo Credits

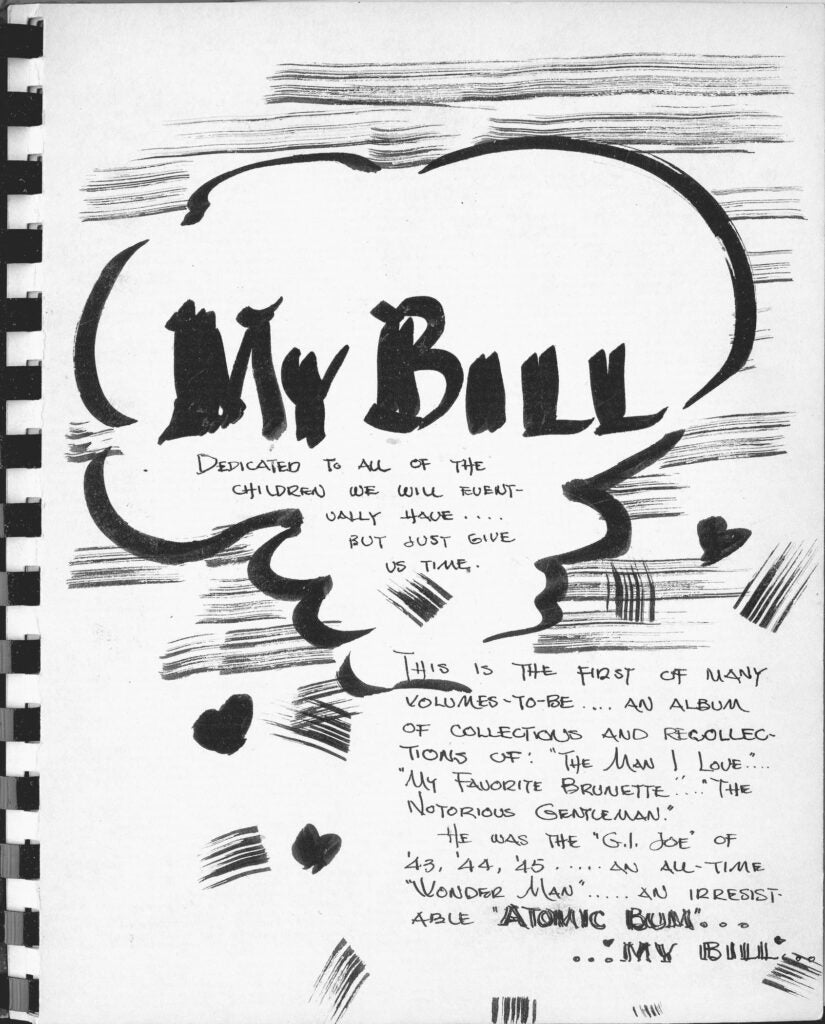

The frontpage of Yuri’s scrapbook “My Bill”. “My Bill. Dedicated to all of the children we will eventually have… but just give us time. This is the first of many volumes-to-be… An album of collections of: “The Man I Love…” “My Favorite Brunette…” “The Notorious Gentleman.” He was the “G.I. Joe” of ’43, ’44, ’45 …. an all-time “wonder Man” … an irresistable “Atomic Bum”… “My Bill”. Photo Credits

Yuri also worked at the USO in the Jerome concentration camp. USOs, or United Service Organizations, existed widely to provide services and entertainment to US soldiers, and continue today.

At the Jerome USO, she met and fell in love with Pvt. Bill Kochiyama, a soldier in the US Army.

Yuri left Jerome to work in the USO in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt rescinded his Executive Order 9066 allowing Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast beginning in January 1945. Yuri and her mother returned to their home in San Pedro.

Yuri, like other Japanese Americans, faced a mixed reception back in California. Some like her neighbors were helpful; others spate racist statements at them. Yuri, for example, worked at different waitressing jobs to earn a living. But inevitably, a customer or co-worker refused to interact with a “Jap” and she was asked to leave.

Yuri and her mom, 1945. With the help of neighbors, Yuri and her mom were able to return to their San Pedro home (893 W. 11th Street) after the war. Photo Credits

Yuri and her mom, 1945. With the help of neighbors, Yuri and her mom were able to return to their San Pedro home (893 W. 11th Street) after the war. Photo Credits