Yuri Kochiyama

Before the War

Mary Yuri Nakahara was born on May 19, 1921, in San Pedro, California, one of three children of immigrants Seiichi Nakahara, a fishmerchant entrepreneur with social connections to the Japanese elite, and Tsuyako “Tsuma” (Sawaguchi) Nakahara, a college-educated homemaker and occasional piano teacher. Kochiyama’s community service began in her youth as a Sunday school teacher and leader of numerous girls’ groups. In the late 1930s, when few Nisei participated in mainstream organizations, Kochiyama became the first female student body officer (vice president) at San Pedro High School and played on the school’s tennis team. She was also a sports writer for the San Pedro News-Pilot. Some contend that her social consciousness began in childhood, where she befriended new students, rooted for the underdog sports team, and had her mother drop her off blocks from school, embarrassed by her family’s relative affluence and fancy car. But Kochiyama denies having any political awareness, stating that she got car sick.

She graduated from high school in 1939 and Compton Junior College in 1941. Years later, her journalism and English majors and art minor served her well as a writer for Movement newspapers and an illustrator of political picket signs. But at the time, her ethical humanitarianism, rooted in Christianity, provided few clues of her later radicalism. Instead, she wanted to marry and have children.

Given her domestic aspirations it is curious that she gained little housekeeping and childcare training, preoccupied instead with extracurricular activities. Her twin brother Peter, who did the most chores, was tolerant of his sister’s limited housework, but her older brother Art was not. Peter attributed his siblings’ conflict to “Mary [being] so different and Art [being] just such a typical Nisei.”1 While lacking any feminist consciousness, her behaviors foreshadowed her rebelliousness and ability to circumvent making housework her individual responsibility.

Wartime Detention

On December 7, 1941, Kochiyama had barely returned home from teaching Sunday school when three FBI agents arrived. Kochiyama’s father, home recovering from ulcer surgery, was whisked away and, unbeknownst to the family for days, detained at the Terminal Island federal penitentiary. Rumors abounded that her father was an enemy spy and Kochiyama was expelled from several organizations. The family believed Nakahara’s arrest arose from his supplying Japanese ships docking in San Pedro harbor and hosting Japanese ship officials at his home. Three other issues were prominent to the FBI. First, FBI records show that Nakahara’s name was found among the papers of Itaru Tachibana, a Japanese naval officer arrested in June 1941 on espionage charges, as a result of Nakahara’s 1937 donation to the Nippon Kaigun Kyokai or Japanese Navy Association. Second, the FBI intercepted a cable declining a visit with Nakahara from his childhood friend Kichisaburo Nomura, the Japanese Ambassador negotiating peace with the US throughout 1941. Third, Nakahara served as head of the San Pedro Japanese Association and the Central Japanese Association of Southern California in the early 1920s.2 None of these activities rendered Nakahara subversive. It is now known that Nakahara was one of 1,300 Japanese American community leaders detained within the first 48 hours of Pearl Harbor. Nakahara’s six-week detention aggravated his health problems and he died on January 21, 1942, the day after his release.

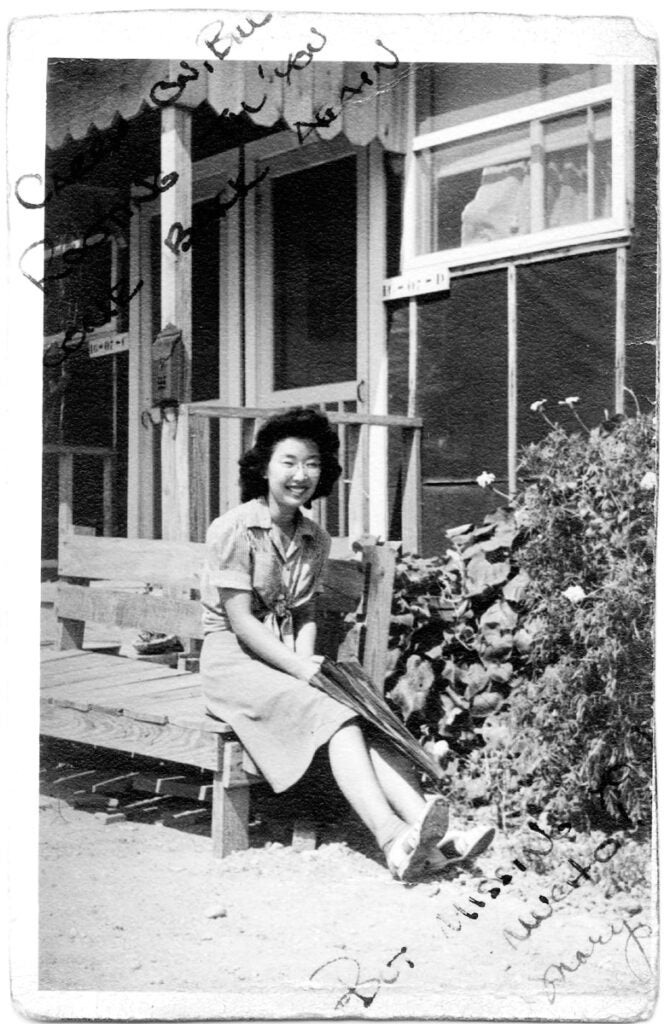

Her father’s premature death and her own incarceration, first at the Santa Anita assembly center and then at Jerome, Arkansas, did not awaken any political outrage in Kochiyama. But she gained racial pride inside the all-Japanese environment, and coped by being of service and keeping busy. She and other young women welcomed new arrivals at the camp’s entrance with upbeat tunes. She also organized her Sunday school teens, the Crusaders, to write to Nisei soldiers, including Kochiyama’s twin brother. In time, the Crusaders—disbursed to camps at Poston, Heart Mountain, Topaz, Rohwer, and Jerome—were sending holiday greetings and letters to some 3,000 Nisei soldiers. One Crusader remembered how Kochiyama’s kindnesses and activities helped offset her deep loneliness. Kochiyama’s gradual awareness of social problems was mixed with ambivalence about being subjected to racism. She wrote in her camp diary: “But not until I myself actually come up against prejudice and discrimination will I really understand the problems of the Nisei.”3

Kochiyama’s correspondence became public news, as she printed excerpts from soldiers’ letters in her Jerome camp newspaper column, “Nisei in Khaki.” She also supported Nisei solders at the Jerome USO, where she met her future husband, the charming and strikingly handsome Pvt. Bill Kochiyama.

Postwar Life

In early 1946, Yuri moved to New York City to marry Bill, recently returned from overseas. They raised six children, Billy, Audee, Aichi, Eddie, Jimmy, and Tommy. The Kochiyamas displayed fairly conventional gender roles, except that their many overnight guests and visitors often helped with housework. They were unusually active in community service, particularly supporting Japanese and Chinese American soldiers enroute to the Korean War. Every Friday and Saturday night, they opened their home for social gatherings, often with a hundred people, half of whom were strangers, crammed into their small housing project apartment. They also published an eight-page family newsletter, Christmas Cheer, annually from 1950 to 1968.

As the Civil Rights Movement grew, Yuri began inviting activists to speak at their open houses. In 1960, a move to Harlem inadvertently expanded their activism. With Yuri as the family’s leading force, the Kochiyamas worked with the Harlem Parent’s Committee, organizing school boycotts to demand quality education for inner-city children. Yuri was among the 600 arrested for blocking the entrance of a construction site to demand jobs for Black and Puerto Rican workers. In October 1963, at a Brooklyn courthouse, she met Malcolm X and boldly inquired if he might support integration. Instead of his transformation, she found herself unexpectedly drawn to his audacious proclamations for Black liberation.

In June 1964, at Yuri’s invitation, Malcolm arrived at the Kochiyamas’s to meet Japanese Hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) and journalists on a world peace tour. She began attending the weekly Liberation School sessions of his Organization of Afro-American Unity. Kochiyama and her oldest son were in the audience at Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom in 1965, when Malcolm X was assassinated. A photograph in Life magazine shows Kochiyama offering comfort to the slain leader, yet there is no mention of her by name or any acknowledgement of an Asian American presence at Malcolm’s talk.

Kochiyama was soon working with the most militant Black nationalist organizations in Harlem, including the Republic of New Africa. When the police and FBI intensified their repression of Black activists, Yuri immersed herself in the struggles to support political prisoners, providing non-stop letter writing—often at two or three in the morning—prison visits, and activist mobilizations. She linked her support for incarcerated activists to her own wartime imprisonment, denouncing the unfairness of U.S. laws and practices.

Though relatively new to activism, the intensity of her work and connections with Black Power made Kochiyama a leader of the emerging Asian American Movement in the late 1960s. In New York City, she joined Asian Americans for Action and was a featured speaker at Hiroshima Day events, denouncing U.S. imperialism in Vietnam, Okinawa, and elsewhere. She supported ethnic studies at the City College of New York and the hiring of Chinese constructions workers at Confucius Plaza. She became a foremost bridge between the Black and Asian movements and between East and West Coast activists. California youth sought her guidance on visits to New York and took her two youngest sons to Los Angeles to live with Yellow Brotherhood activists. Her older children were active in the Asian American and Third World movements.

In the 1980s, Bill, who headed the media committee, and Yuri organized with Concerned Japanese Americans and later the East Coast Japanese Americans for Redress to demand that New York be added as a site of a Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) hearings. During Bill’s testimony in New York, Yuri and others defiantly marched in with political art, previously banned by CWRIC. Yuri testified before CWRIC in Washington D.C. She continues to link this victory to calls for Black reparations and her wartime experiences to oppose the post-9/11 “war on terrorism.”

Kochiyama was one of the most prominent Asian American activists of the 20th century. Her life is featured in her memoirs, Passing It On (2004); the biography, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama (2005); and two documentaries, Yuri Kochiyama: Passion for Justice (1993) and Mountains that Take Wing (2009), as well as in hundreds of articles and films. She is revered for her six decades of intensive social justice commitments and for her compassionate focus on the individuals involved in the movement.4

Footnotes

- Diane C. Fujino, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 19.

- FBI file of Seiichi Nakahara, Aug 27, 1941; Dec 6, 1941; Dec 23, 1941; Jan 23, 1942; June 22, 1943; Kenji Murase, “An ‘Enemy Alien’s’ Mysterious Fate,” National Japanese American Historical Society (winter 1997), 4-5, 14.

- Kochiyama diary, vol. 2, September 9, 1942.

- Diane C. Fujino, “Grassroots Leadership and Afro-Asian Solidarities: Yuri Kochiyama’s Humanizing Radicalism,” in Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle , eds. Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 294-316.

Credit: Fujino, Diane. Yuri Kochiyama. Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved on October 9, 2019 from https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Yuri_Kochiyama/.