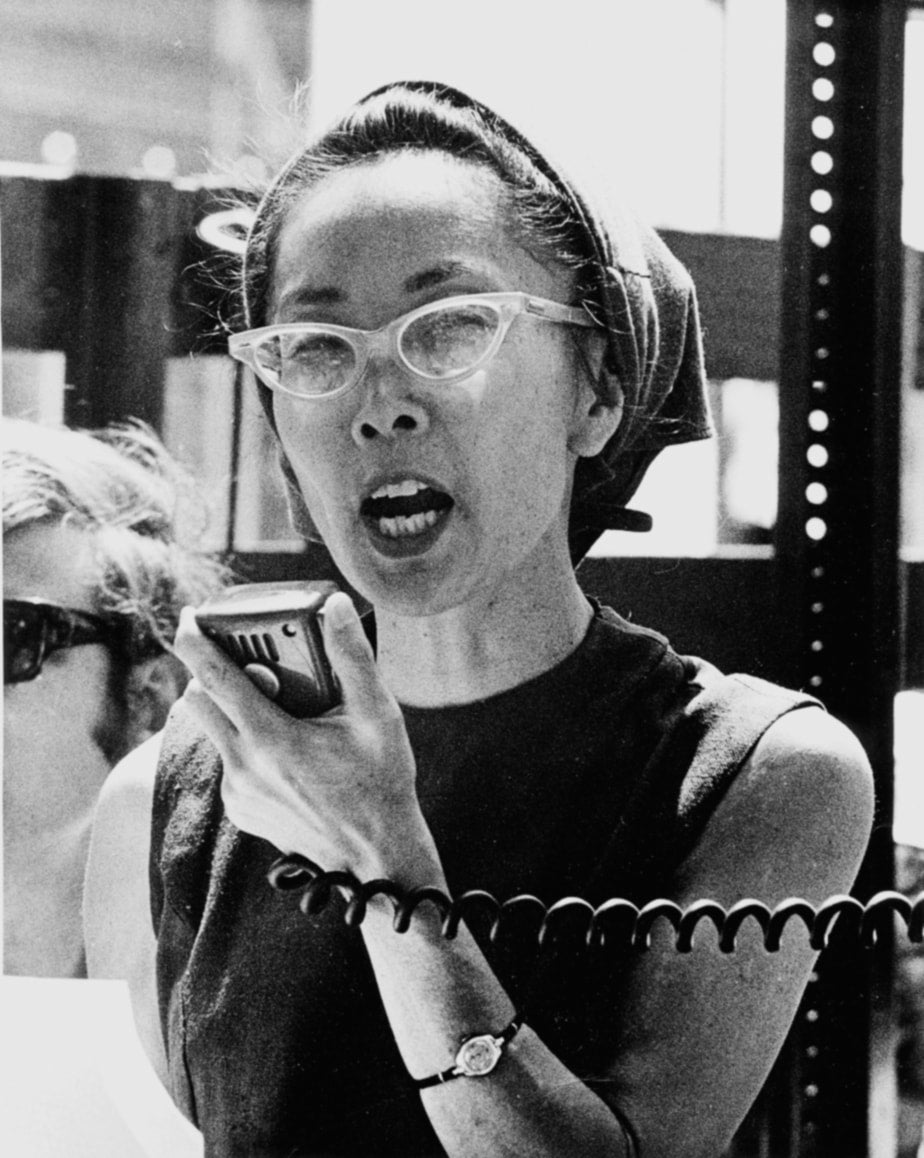

YURI KOCHIYAMA

Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014) is one of the most distinguished Asian American activists of the 20th century. She is best known for her work promoting Afro-Asian solidarity.

Her experiences living in US concentration camps during World War II gradually shaped her social consciousness. During the 1950s, she supported Asian American issues and followed the events of the emerging Civil Rights Movement. In 1960, Yuri, her husband, and six children moved to Harlem. There Yuri got involved in the Black movement and met Malcolm X.

She became a foremost leader in the Asian American Movement and a proponent of Asian-Black solidarity. Yuri is a renowned for her dedicated activism spanning more than 50 years and as a model of the collective care in movement organizing.

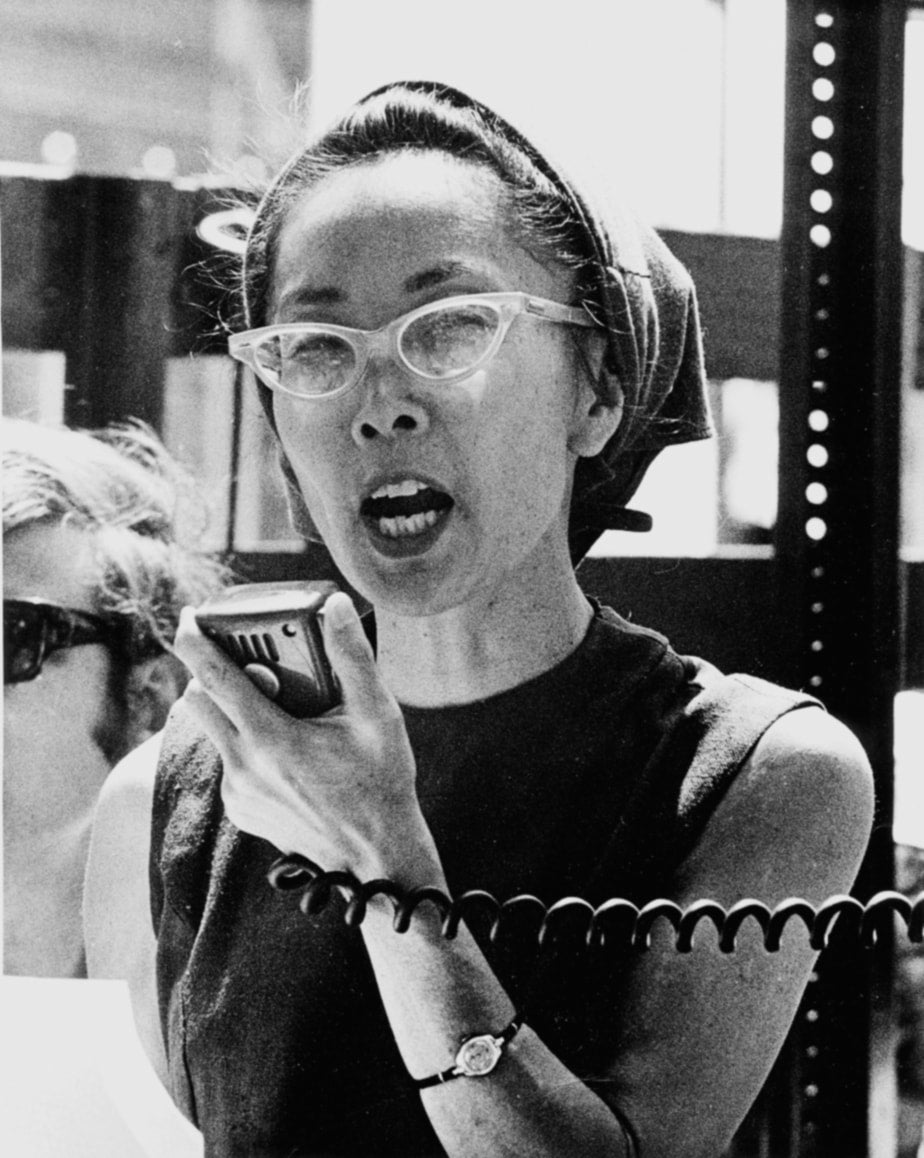

YURI KOCHIYAMA

Yuri Kochiyama (1921-2014) is one of the most distinguished Asian American activists of the 20th century. She is best known for her work promoting Afro-Asian solidarity.

Her experiences living in US concentration camps during World War II gradually shaped her social consciousness. During the 1950s, she supported Asian American issues and followed the events of the emerging Civil Rights Movement. In 1960, Yuri, her husband, and six children moved to Harlem. There Yuri got involved in the Black movement and met Malcolm X.

She became a foremost leader in the Asian American Movement and a proponent of Asian-Black solidarity. Yuri is a renowned for her dedicated activism spanning more than 50 years and as a model of the collective care in movement organizing.

Remember that consciousness is power. Consciousness is education and knowledge. Consciousness is becoming aware. It is the perfect vehicle for students. Consciousness-raising is pertinent for power, and be sure that power will not be abusively used, but used for building trust and goodwill domestically and internationally. Tomorrow’s world is yours to build.

-Yuri Kochiyama-

Mary Yuri Nakahara was born on May 19, 1921, in San Pedro, CA, the child of immigrants from Japan. Her father, Seiichi Nakahara, was a fishmerchant entrepreneur with social connections to the Japanese elite, and her mother, Tsuyako “Tsuma” (Sawaguchi) Nakahara, was a college-educated homemaker and occasional piano teacher.

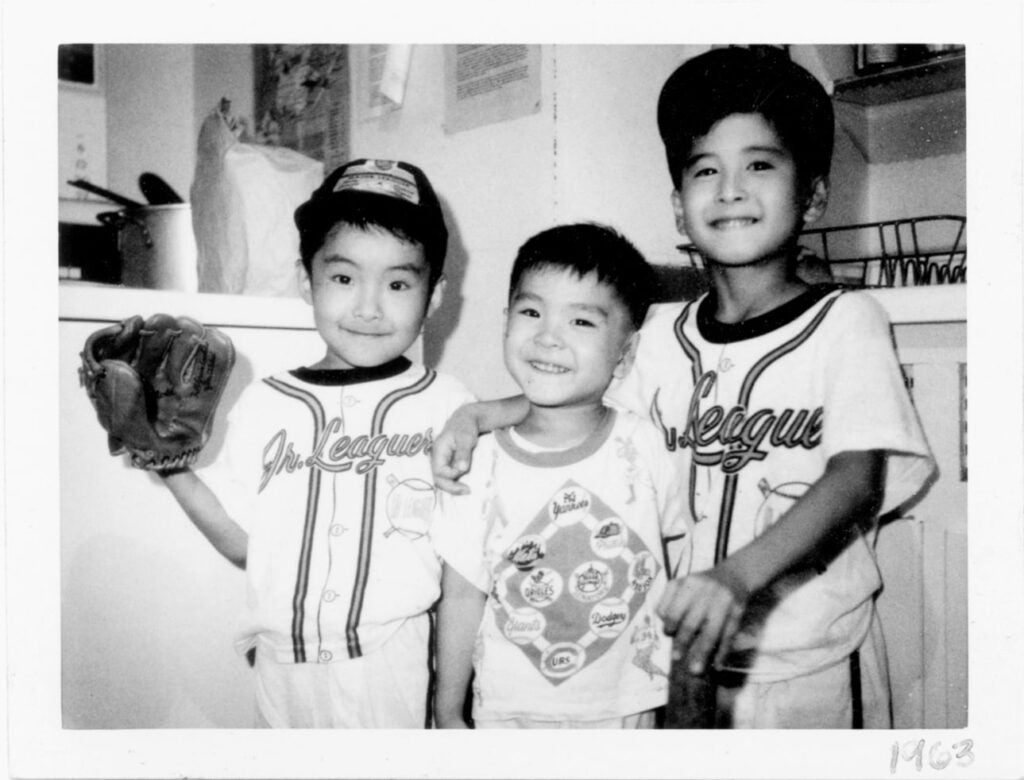

The Nakahara family at their San Pedro home, circa 1924. Tsuya (left) and Seiichi (right) with children Yuri, Pete and Arthur. Photo Credits

The Nakahara family at their San Pedro home, circa 1924. Tsuya (left) and Seiichi (right) with children Yuri, Pete and Arthur.

Mary Yuri Nakahara was born on May 19, 1921, in San Pedro, CA, the child of immigrants from Japan. Her father, Seiichi Nakahara, was a fishmerchant entrepreneur with social connections to the Japanese elite, and her mother, Tsuyako “Tsuma” (Sawaguchi) Nakahara, was a college-educated homemaker and occasional piano teacher.

She grew up with her older brother, Art, and her twin brother, Pete. They were part of the “Nisei” generation, or children of Japanese immigrants.

Despite their middle-class comforts, her family experienced residential segregation and other forms of racism. Anti-Japanese racism was widespread even before World War II.

The Nakahara family in their San Pedro home, 1938.

(From left) Arthur, Seiichi, Peter (standing), Yuri, and Tsuya. Photo Credits

The Nakahara family in their San Pedro home, 1938.

(From left) Arthur, Seiichi, Peter (standing), Yuri, and Tsuya. Photo Credits

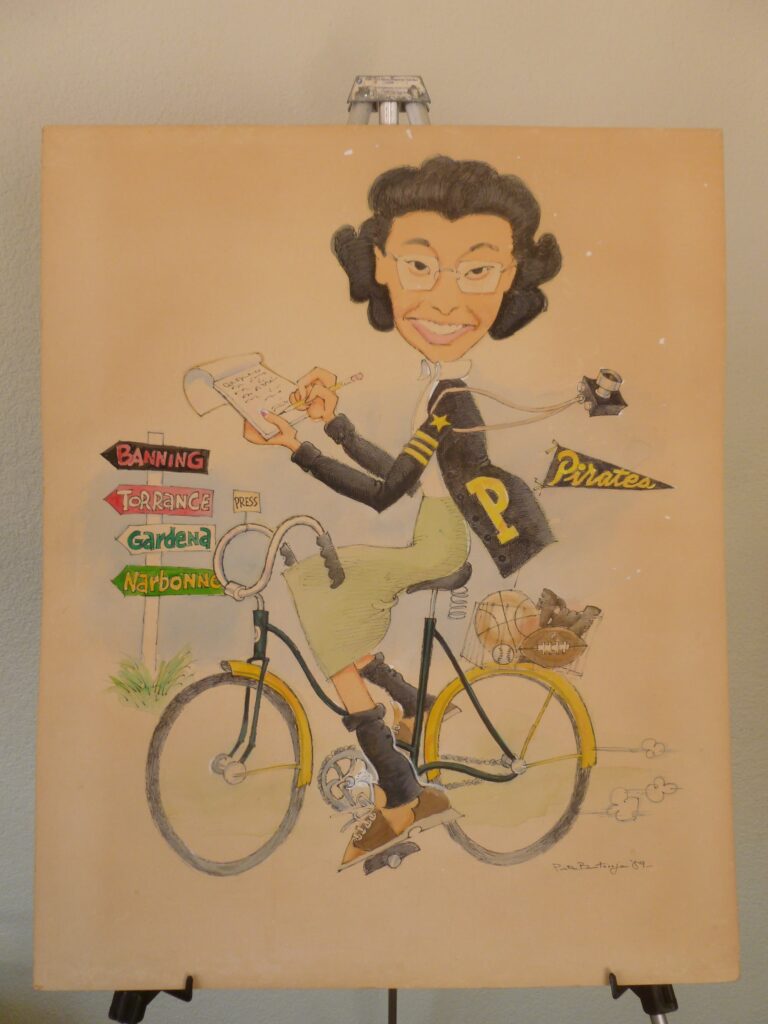

This caricature depicts Yuri’s numerous travels by bicycle to cover San Pedro High School sporting events for the San Pedro News-Pilot. Artist, Peter Bentovoja. Courtesy of Norma L. Brutti. Source: Heartbeat of Struggle. Photo Credits

Growing up, Yuri was actively involved in community service and extracurricular activities. This was a time when racism excluded the participation of most Nisei in mainstream organizations.

When she later gained an awareness of racism, these experiences would have an impact on her.

Yuri graduated from San Pedro High School in 1939 and Compton Junior College, with a major in journalism and minor in art, in 1941.

This caricature depicts Yuri’s numerous travels by bicycle to cover San Pedro High School sporting events for the San Pedro News-Pilot. Artist, Peter Bentovoja. Courtesy of Norma L. Brutti. Source: Heartbeat of Struggle. Photo Credits

Yuri’s life changed dramatically on December 7, 1941. That same day, the FBI came to arrest her father and about 1,300 other Japanese Americans. Nobody knew where these men were taken or what would happen to them.

While the US claimed that those arrested were threats to national security, this was not true. Instead those arrested tended to be community leaders or businessmen with connections to Japan.

Yuri’s father had recently had ulcer surgery when the FBI agents took him away.

His health greatly deteriorated during his six weeks in detention. The government released him only when he was near death. Mr. Nakahara died the next day, on January 21, 1942, at his family home. He was 54 years old.

Seiichi Nakahara and Tsuya Sawaguchi’s wedding picture, 1917 Photo Credits

Seiichi Nakahara and Tsuya Sawaguchi’s wedding picture, 1917 Photo Credits

The problems for Japanese Americans did not begin with Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor. As early as 1900, an anti-Japanese movement began to grow. This included White supremacists wanting to “Keep California White.”

There were many laws that discriminated against Japanese Americans, including the Alien Land Act of 1913 barring Japanese Americans from purchasing land and the Immigration Act of 1924 banning immigration from Japan. Photo Credits

Yuri too experienced anti-Japanese racism. She couldn’t believe that people began to see her as suspect, this in her hometown where she seemed to have been so accepted.

Yuri’s twin brother, Pete, decided he wanted to join the US Army. It was a confusing time, with Mr. Nakahara accused of being a danger to national security, while his son was allowed to serve in the US Armed Forces. Photo Credits

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. In the Spring of 1942, the US military began posting “evacuation notices,” giving one week’s notice to all Japanese American families in California and parts of Washington, Oregon, and Arizona. Photo Credits

Yuri, her brother Art and her mother, like the other 110,000 Japanese Americans, had to pack their belongings and prepare to leave. They were allowed to take only what they could carry. Yuri was 20 years old. Photo Credits

Yuri and her family were sent to the Santa Anita “assembly center.” The conditions were harsh. Their new “home” smelled like the horses that had just recently lived there. They were forbidden from leaving.

Yuri stayed active, in part as a way to cope. She continued to teach Sunday School and also worked as a nurse’s aid for the meager $8 a month.

After seven months, Yuri and her family were moved to Jerome, Arkansas, one of the ten more permanent concentration camps. Photo Credits

In Santa Anita, and continuing in Jerome, Yuri transformed her Sunday School class into a letter writing campaign to support Japanese Americans in the US military.

The Crusaders, as they named themselves, were soon writing to hundreds of soldiers as well as to Japanese American orphans and tuberculosis patients.

The Junior Junior Crusaders at Jerome AK internment camp, welcoming Nisei GI’s visiting from Fort Harrison, Indiana (circa 1944). Photograph taken by one of the Fort Harrison Nisei soldiers. Photo Credits

Yuri’s mom (kneeling, second from right) with Senior Crusaders. Jerome, Arkansas internment camp, circa 1944. Photo Credits

In Jerome, Yuri printed excerpts from soldiers’ letters in her Jerome camp newspaper column, “Nisei in Khaki.”

This letter is from a Nisei soldier stationed in Italy, written to Mrs. Nakahara in the Jerome concentration camp. He affectionally calls her “mom.” Mrs. Nakahara actively supported the young women in their letter writing to Nisei soldiers.

Missing Image: From Yuri’s Archives, Batch 2, notebook 3. Slide 14

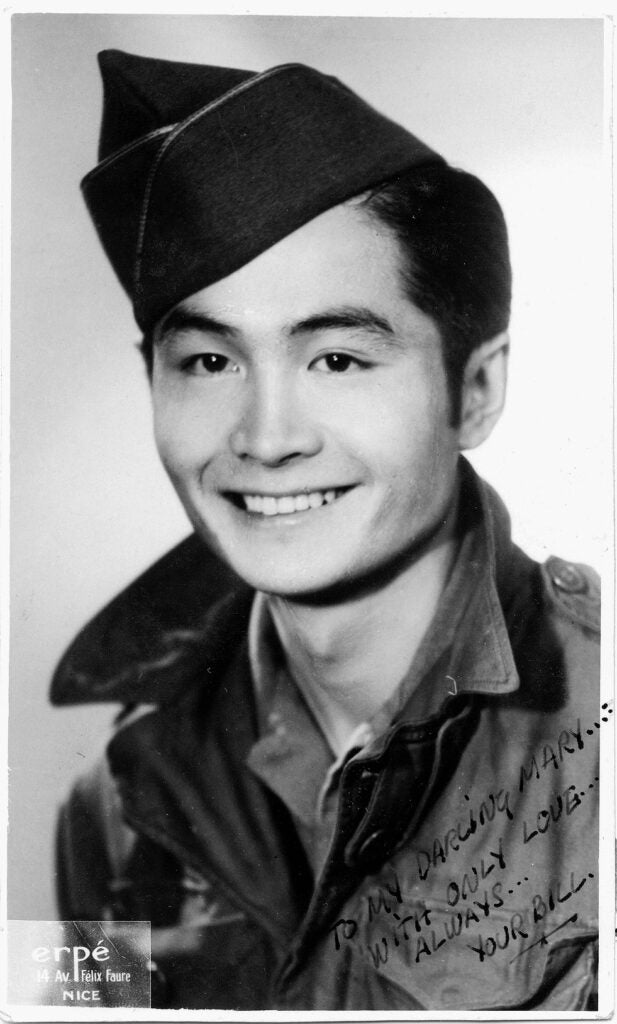

Bill in uniform, France 1944. Photo Credits

Yuri also worked at the USO in the Jerome concentration camp. USOs, or United Service Organizations, existed widely to provide services and entertainment to US soldiers, and continue today.

At the Jerome USO, she met and fell in love with Pvt. Bill Kochiyama, a soldier in the US Army.

Yuri left Jerome to work in the USO in Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

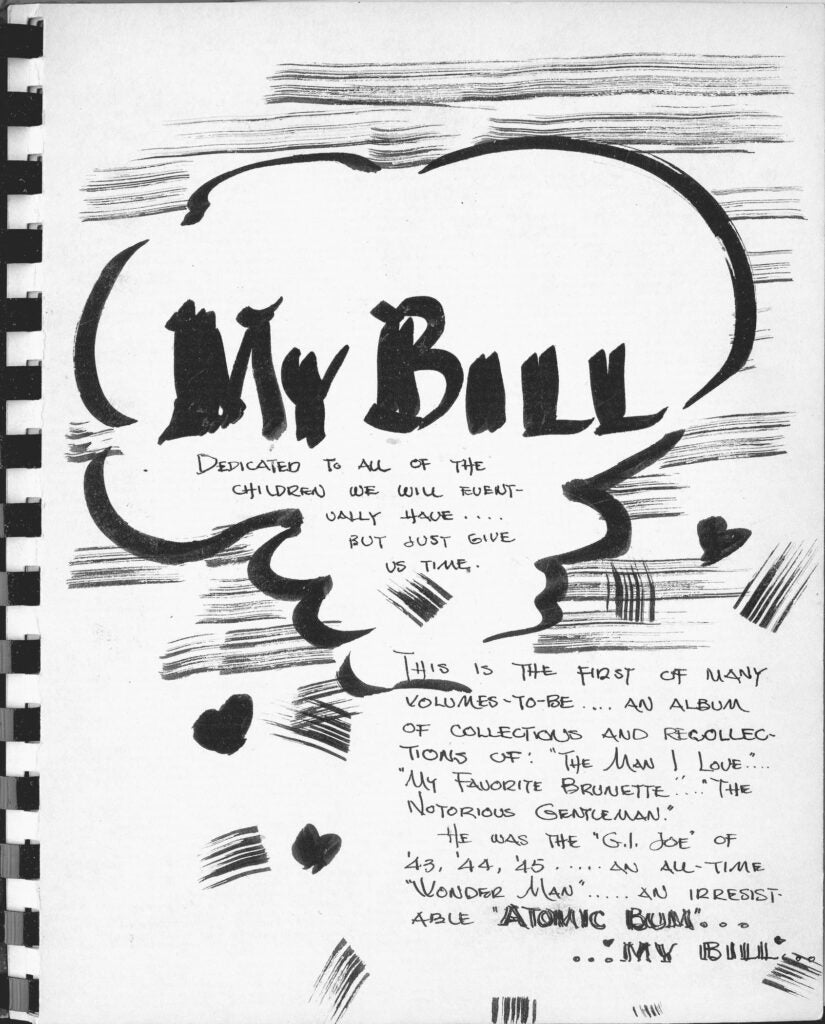

The frontpage of Yuri’s scrapbook “My Bill” Photo Credits

When a US Supreme Court allowed Japanese Americans to return to the West Coast, Yuri and her mother returned to their San Pedro home.

Yuri, like other Japanese Americans, faced a mixed reception back in California. Some like her neighbors were helpful; others spate racist statement at them. Yuri, for example, worked at different waitressing jobs to earn a living. But inevitably, a customer or co-worker refused to interact with a “Jap” and she was asked to leave.

Yuri and her mom, 1945. With the help of neighbors, Yuri and her mom were able to return to their San Pedro home (893 W. 11th Street) after the war. Photo Credits

Yuri and her mom, 1945. With the help of neighbors, Yuri and her mom were able to return to their San Pedro home (893 W. 11th Street) after the war. Photo Credits

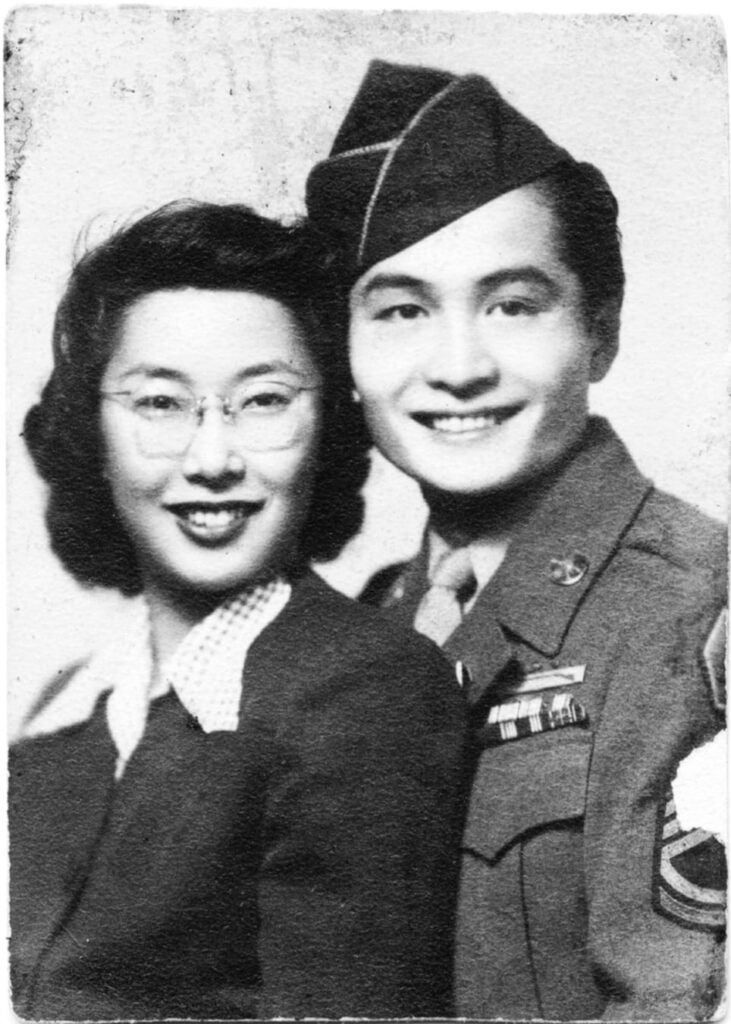

When her finance Bill Kochiyama return from the warfront in Europe, Yuri excitedly traveled to meet him in New York City, where he had grown up. They married on February 9, 1946.

Yuri and Bill would go on to have six children: Billy, Audee, Aichi, Eddie, Jimmy, and Tommy. They provided an active life for their children, who participated in sports, especially their beloved baseball, Boys Scouts, Girls Scouts, and the Presbyterian Christian church. Her children also had opportunities to dance and model professionally or serve as extras in television shows.

In the 1950s, Yuri and Bill were active in community service. They worked to support Nisei veterans as well as Japanese and Chinese American soldiers being sent to the Korean War.

They also opened their home for social gatherings, often with a hundred people crammed into their apartment every weekend, including the Nisei-Sino Service Organization (NSSO), pictured here.

The Kochiyama family opened its home to the Nisei-Sino Service Organization on Friday nights (early 1950s). Photo Credits

The Kochiyama family opened its home to the Nisei-Sino Service Organization on Friday nights (early 1950s). Photo Credits

Slide 22. Missing 2 images from repository.

The NSSO visited and organized dances for the “Hiroshima Maidens.” These young women spend a year in New York undergoing reconstructive surgeries and recovering from the disfiguring and painful impact of the US atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

The Kochiyamas published an eight-page family newsletter, Christmas Cheer, every year from 1950 to 1968. Here is a page featuring a story on the Hiroshima Maidens.

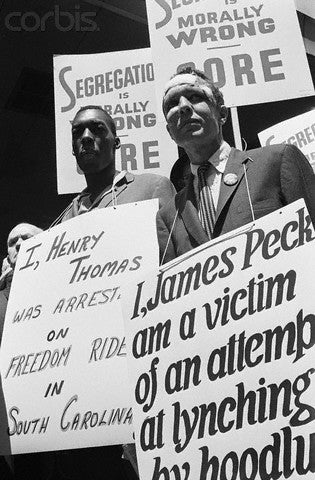

17 May 1961, Manhattan, New York, New York, USA — 5/17/1961-New York, NY: James Peck (R) marches in a picket line outside the Trailways Bus Station, in the Port Authority Terminal. Peck was severely beaten on May 14th in Birmingham, AL, when a mob assaulted passengers of a bus containing “Freedom Riders,” a group trying to break down segregation barriers in inter-state bus terminals as decreeed by the Supreme Court. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS Photo Credits

As the Civil Rights Movement grew, Yuri began inviting activists to speak at the Kochiyama’s weekend open houses.

One particularly moving visitor was James Peck, who in 1961, traveled as part of interracial Black-White teams to protest the non-enforcement of desegregation laws.

White mobs violently beat the Freedom Riders at many stops. James Peck himself was beaten so badly, he required 57 stitches.

17 May 1961, Manhattan, New York, New York, USA — 5/17/1961-New York, NY: James Peck (R) marches in a picket line outside the Trailways Bus Station, in the Port Authority Terminal. Peck was severely beaten on May 14th in Birmingham, AL, when a mob assaulted passengers of a bus containing “Freedom Riders,” a group trying to break down segregation barriers in inter-state bus terminals as decreeed by the Supreme Court. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS Photo Credits

In 1960, the Kochiyamas moved to Harlem. Harlem was a Black community steeped in a tradition of fervent Black political and cultural resistance.

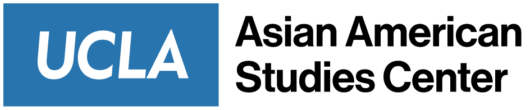

Yuri and her family worked with the Harlem Parent’s Committee, organizing school boycotts to demand quality education for inner-city children. Hundreds of thousands of students and more than 3,500 teachers supported the boycott. Photo Credits

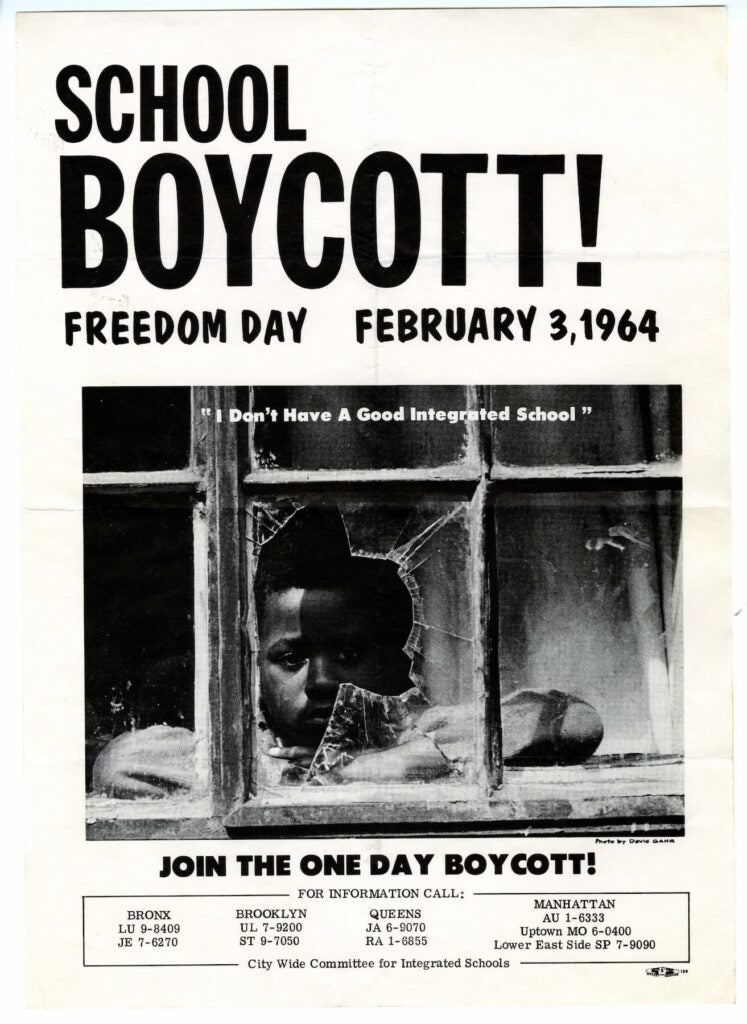

In October 1963, Yuri met the person who would transform her life, Malcolm X. When she walked up to him, she surprised that she speak so candidly. She said, “I admire the kinds of things you’re saying, but I don’t agree with you about something…Your harsh stance on integration.”

Malcolm X’s response was not harsh or dismissive, but instead he invited her to attend his newly formed Organization of Afro-American Unity’s Liberation School every Saturday morning. Photo Credits

What Yuri learned at the OAAU Liberation School significantly shaped her thinking about racism.

One day, she heard a recording of Fannie Lou Hamer, the renowned leader of the Southern voting rights struggles, describing the life of poverty that she and other poor Black people experienced in Mississippi.

It was especially disturbing to hear Hamer, who like Yuri was a middle-aged mother, describe how White prison guards pressured two Black male prisoners to viciously beat her in prison.

Yuri’s ideas were changing quickly. She was no longer seeing racism as individual attitudes and bigotry, but instead as a structural problem, as embedded in the very institutions and history of society. Photo Credits

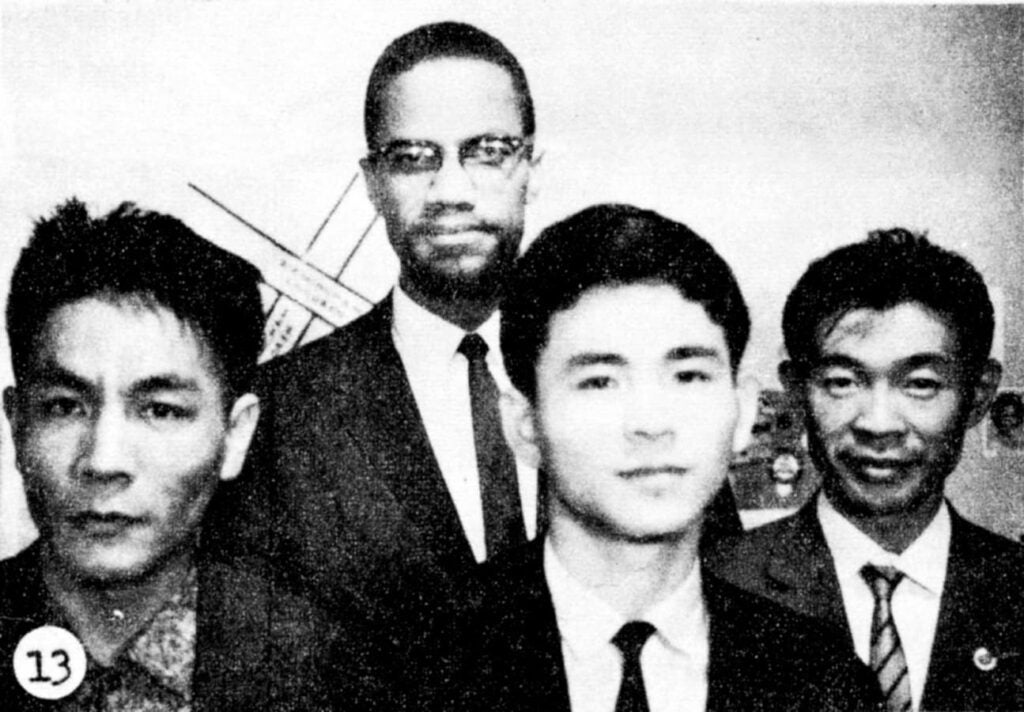

At Yuri’s invitation, Malcolm X came to the Kochiyama’s home to meet Japanese Hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) and journalists traveling on a world peace tour. The meeting was held at the Kochiyama home in Harlem, on June 6, 1964.

Photos:

(From left) Ryuji Hamai (writer), Nobuya Tsuchida (interpreter), and Akira Mitsui

(reporter)—delegates of the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Study Mission.

photograph From Christmas Cheer, Volume 15 (1964), p. 6. Photo on the right: Malcolm X with Yuri’s daughter, Audee, and three other teens from the same event.

While traveling in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe in 1964, Malcolm X send the Kochiyamas eleven postcards. This one is postmarked from Cairo.

One of eleven postcards Malcolm X sent to the Kochiyamas from his travels. This one is postmarked from Cairo. Photo Credits

One of eleven postcards Malcolm X sent to the Kochiyamas from his travels. This one is postmarked from Cairo. Photo Credits

Yuri and her oldest son were in the audience at Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom in February 1965, when Malcolm X was assassinated. A photograph in Life magazine shows Yuri offering comfort to the slain leader, yet there is no mention of her by name or any acknowledgement of an Asian American presence at Malcolm’s talk.

This is the only known image of Yuri and Malcolm together. But in later years, especially after Yuri’s passing in 2014, artists and activists would create numerous posters, murals, and images jointly featuring Yuri and Malcolm.

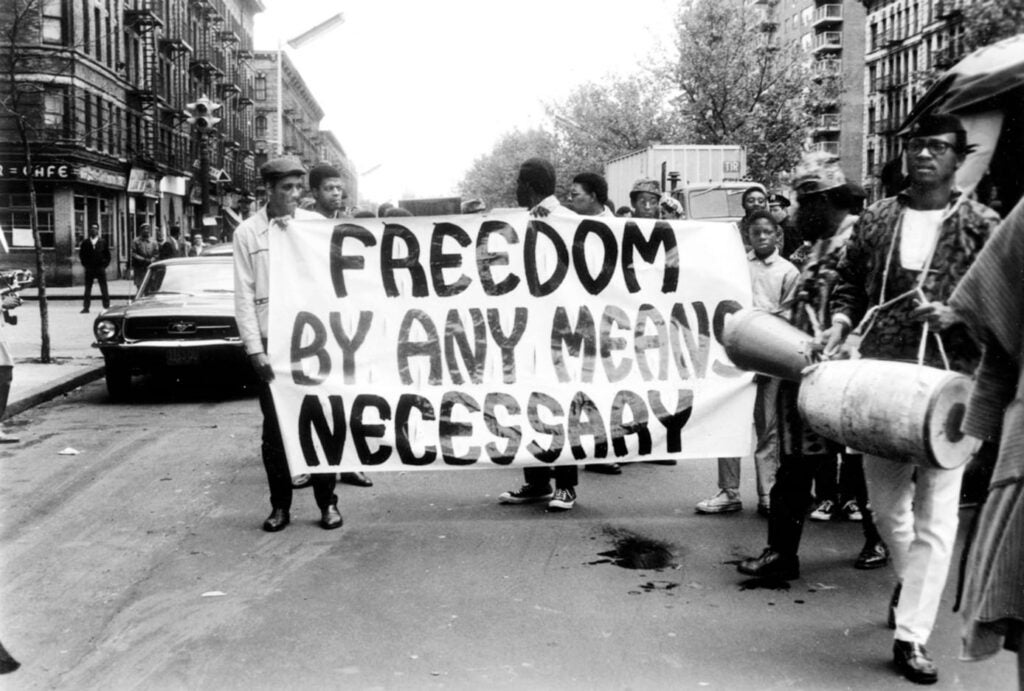

Organization of African American Unity at a rally commemorating the life of Malcolm X, Harlem (circa 1965) Photo Credits

Following the assassination of Malcolm X, a number of Black organizations formed to carry forward Malcolm’x vision for Black liberation. Having been associated with Malcolm’x people at the OAAU, Yuri was soon working with the most militant Black nationalist organizations in Harlem, including the Republic of New Africa.

Organization of African American Unity at a rally commemorating the life of Malcolm X, Harlem (circa 1965) Photo Credits

In the 1960s, the police and FBI intensified their surveillance of Black activists. Yuri’s friends and fellow activists were targeted and arrested, often because their activism challenged the established order. Yuri immersed herself in the political prisoner movement. She constantly wrote letters to prisoners, visited people in prison, and helped to organize campaigns for their release.

Yuri came to be regarded as a central person in the struggle to free and support political prisoners.

Her own experiences with wartime incarceration experiences, and the injustices involved, fueled her work.

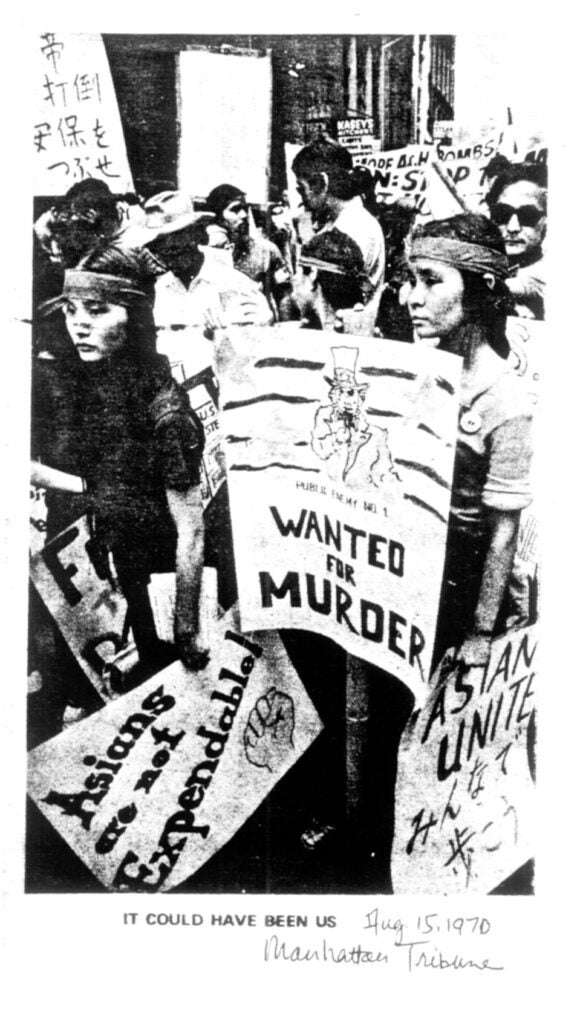

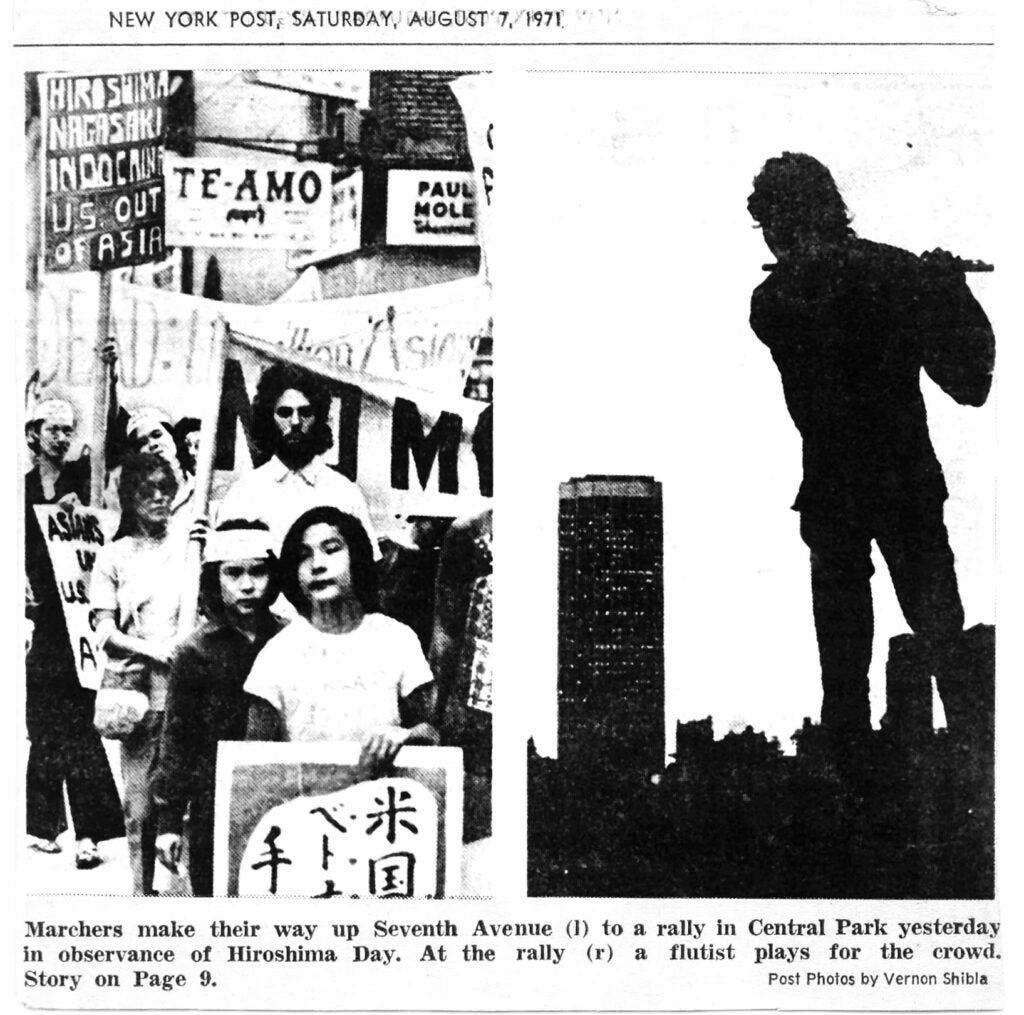

Asian Americans demonstrating in Manhattan against the Vietnam War. Photo by Yuri Kochiyama Photo Credits

As the Asian American Movement emerged nationwide in the late 1960s, Yuri joined Asian Americans for Action in New York City. She was a featured speaker at Hiroshima Day events, opposing US militarism and imperialism in Vietnam, Okinawa, and elsewhere.

Yuri supported ethnic studies at the City College of New York and the hiring of Chinese constructions workers at Confucius Plaza.

Asian Americans demonstrating in Manhattan against the Vietnam War. Photo by Yuri Kochiyama Photo Credits

Yuri’s children were active in various struggles for justice.

Yuri came to be seen as one of the most prominent Asian American activists and since the late 1960s, Asian Americans from throughout the nation have visited her in New York. She became a foremost bridge between East Coast and West Coast Asian American activists and between the Black and Asian movements.

Yuri and Bill got involved in the nationwide movement for Japanese American redress and reparations in the 1970s and 1980s. Bill and Yuri helped to found the East Coast Japanese Americans for Redress (ECJAR). Bill testified at the Congressional hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) in New York City, and Yuri did so in Washington DC.

Yuri consistently called for Black reparations alongside the demand for Japanese American redress.

New York Chapter of the David Wong Committee, 1994. Picture of Bill (center); Yuri and Kazu Iijima (seated at right). Photo Credits

Asians for Mumia, New York City, 1996. Yuri was a strong supporter of Mumia Abu-Jamal, the renowned political prisoner and former Black Panther, since his arrest and imprisonment in the early 1980s. When Mumia was facing the death sentence in 1995, Yuri formed Asians for Mumia and drew Asian Americans into the struggle for political prisoners. Photo Credits

In the 1990s, Yuri Kochiyama grew to national prominence as one of the most influential Asian American activists of the 20th century. Asian American college students across the nation began inviting her to be their featured speaker.

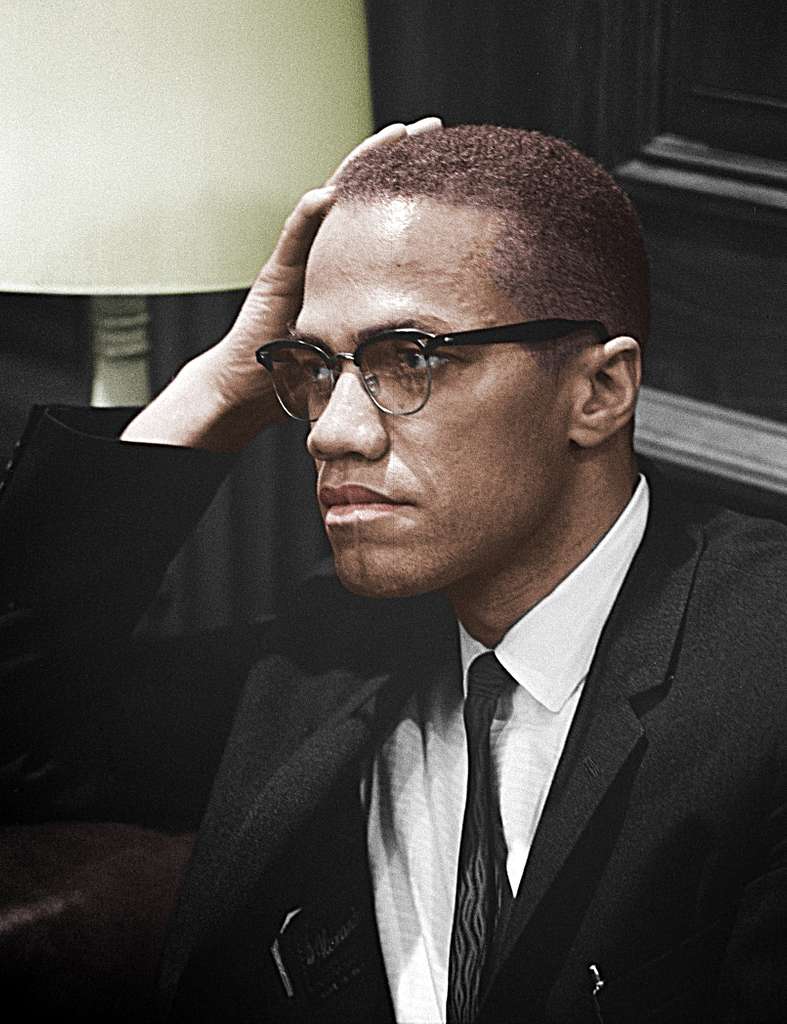

Two documentaries center Yuri’s activism:

* Rea Tajiri and Pat Saunders”s documentary, “Yuri Kochiyama: Passion for Justice” (1993).

* C.A. Griffith and H.L.T. Quan’s “Mountains that Take Wings: Angela Davis & Yuri Kochiyama: A Conversation of Life, Struggle, and Liberation” (2009).

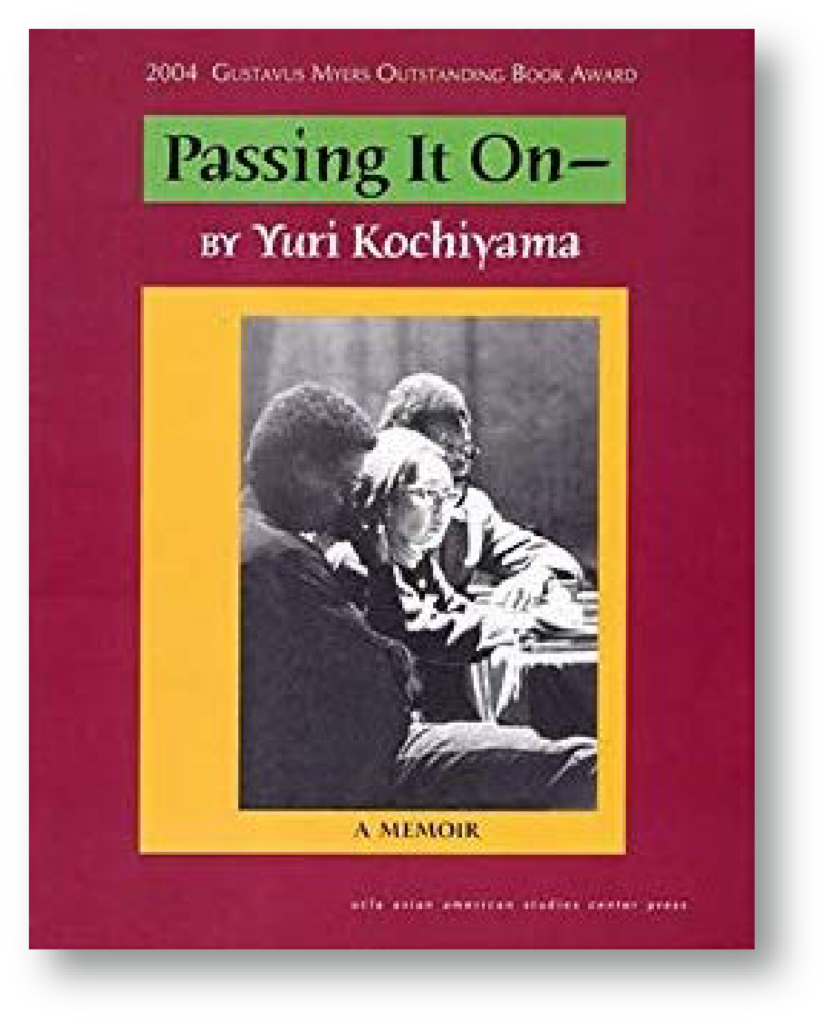

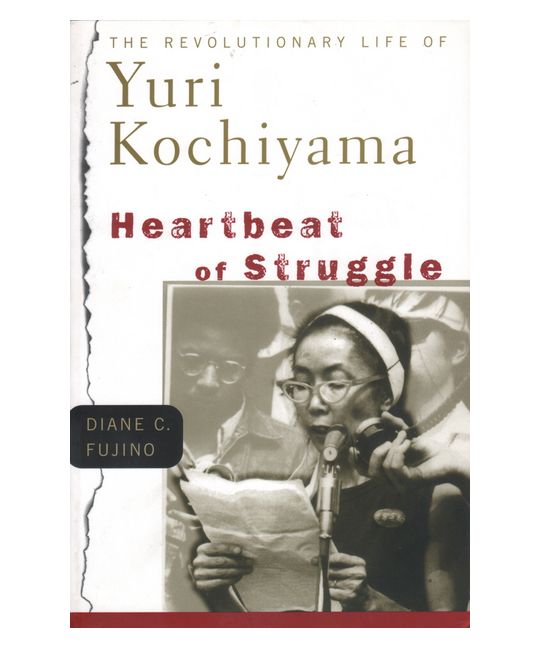

Two books focus on Yuri’s activism and life:

* UCLA Asian American Studies Center published Yuri Kochiyama’s memoir, Passing It On, edited by Marjorie Lee, Akemi Kochiyama-Sardinha, and Audee Kochiyama-Holman (2004).

* Diane Fujino’s political biography, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama (University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

Yuri, Angela Davis and Akemi Kochiyama-Sardinha, October 1997. Angela Davis moderated the African/Asian Round Table at San Francisco State University Photo Credits

Yuri’s impact on political activism and popular culture is tremendous, including:

* The Blues Scholars’s song, “Yuri Kochiyama”

* The corporate giant, Google, recognized Kochiyama with a google doodle in 2016.

* The Asian American Women Artists Association curated an art exhibition, “Shifting Movements: Art Inspired by the Life & Activism of Yuri Kochiyama,” San Francisco, 2016.

* The Asian Law Caucus established the annual Yuri Kochiyama Impact Award.

Working against the ongoing invisibility of Asian American activism, countless people across the nation are invoking Yuri Kochiyama as a legendary Asian American activist. Her renowned only increased for a new generation in the wake of the Movement for Black Lives and new waves of anti-Asian violence during the Covid-19 pandemic. Photo Credits

References

Diane C. Fujino, Heartbeat of Struggle: The Revolutionary Life of Yuri Kochiyama. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2005

Diane C. Fujino, “Grassroots Leadership and Afro-Asian Solidarities: Yuri Kochiyama’s Humanizing Radicalism.” In Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle., ed. Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard, 294-316. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

C.A. Griffith and H.L.T. Quan. Mountains that Take Wing: Angela Davis and Yuri Kochiyama. Documentary, 2009.

Yuri Kochiyama, Passing It On–A Memoir. Edited by Marjorie Lee, Akemi Kochiyama-Sardinha, and Audee Kochiyama-Holman. Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 2004.

Yuri Kochiyama, speeches, UCLA Asian American Studies Center.

NPR, Throughline podcast, “Our Own People”.

Rea Tajira and Pat Saunders. Yuri Kochiyama: Passion for Justice. Documentary, 1993.

Hansi Lo Wang (August 19, 2013). “Not Just A ‘Black Thing’: An Asian-American’s Bond With Malcolm X”. NPR, Code Switch podcast.